Myeloma (or multiple myeloma) is a cancerous, uncontrolled growth of a type of immune cell called a plasma cell. Plasma cells produce proteins called antibodies that provide long-lasting immunity to infection. Read more about the role of plasma cells. In myeloma, illness is due to having too many plasma cells in the bone marrow. These cells damage many organs by their vast over-production of antibodies.

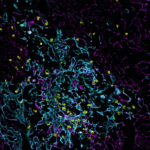

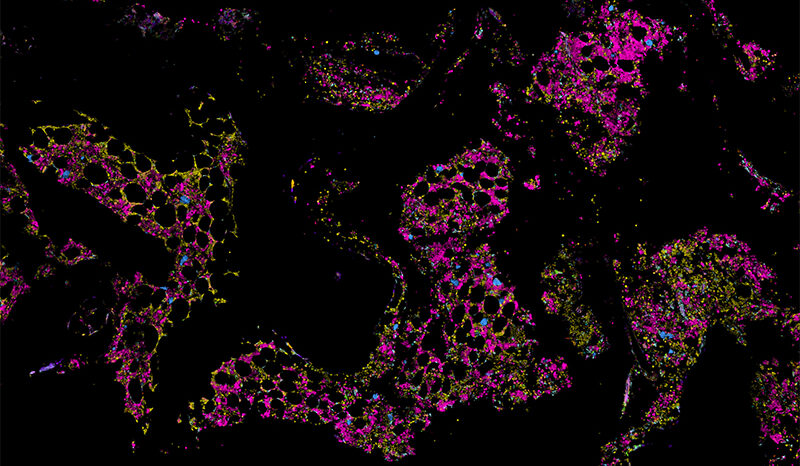

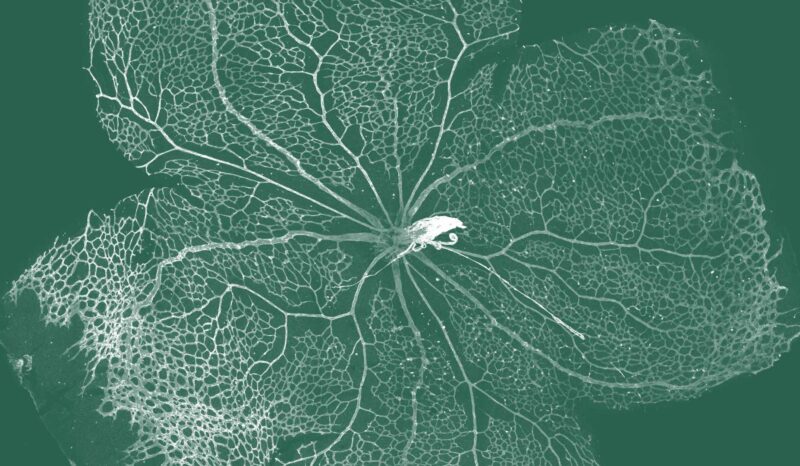

Plasma cells are found in the bone marrow of large bones, along with other cells that form blood (such as stem cells and progenitor cells), other immune cells and bone-forming cells. Normally the numbers of each cell type are tightly controlled.

Myeloma occurs when a plasma cell spontaneously undergoes changes to its genetic material (DNA) that allow it to divide uncontrollably and become independently long-lived. These cancerous plasma cells can then accumulate in the bone marrow.

Because myeloma develops from a single plasma cell, the large amounts of antibody protein produced by the cancer are all essentially identical. This is called a monoclonal protein or M-protein as it comes from one clone or cell. This protein can ‘thicken’ the blood, causing circulatory problems. It can also replace normal antibodies that fight infections. High levels of M protein also lead to kidney damage.

Within the bone marrow, myeloma cells crowd out normal cells. This prevents the ongoing renewal of blood cells. The myeloma cells also impair the formation and repair of bone by stimulating cells that destroy bone.

People with myeloma often experience:

- Anaemia: too few oxygen-carrying red blood cells in the blood

- Immune deficiency: too few immune cells and too little normal antibody in the blood

- Problems with blood clotting: because platelet production in the bone marrow is hampered.

- Bone weakness, caused by the destruction of the bone.

- High levels of calcium in the blood, caused by bone destruction.