Earlier diagnosis and better treatments have seen a doubling in survival rates from bowel cancer in Australia over the past 40 years.

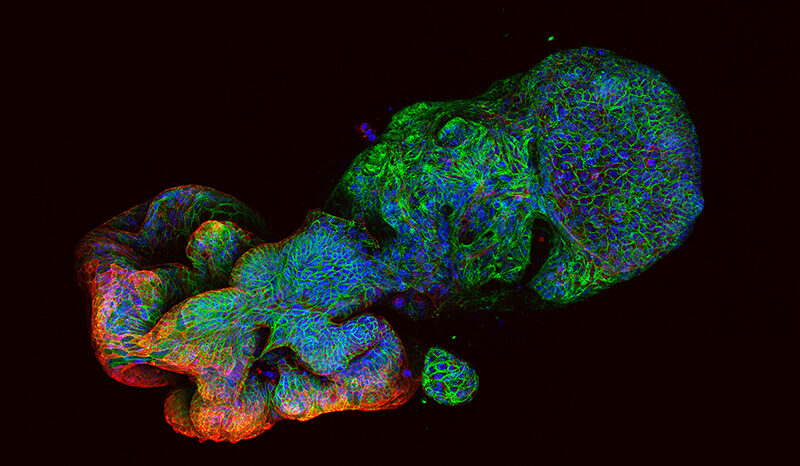

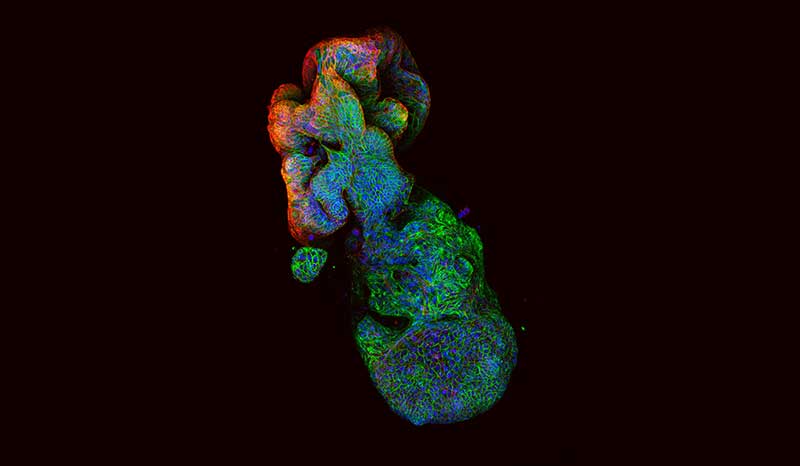

When bowel cancer is detected early, before it has spread outside the bowel, it can often be cured by using surgery to remove the section of the bowel that contains the cancer.

When the cancer has spread outside the bowel (metastatic bowel cancer), surgery is usually combined with other treatments to kill any remaining cancer cells. Chemotherapy is an important part of treatment for metastatic bowel cancer. Several different chemotherapy drugs are used to treat bowel cancer, either alone or in combinations of two or more drugs.

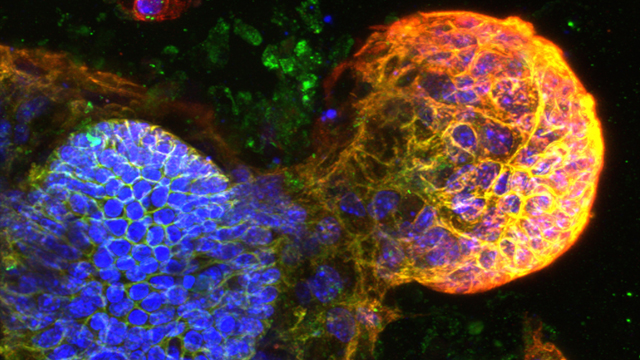

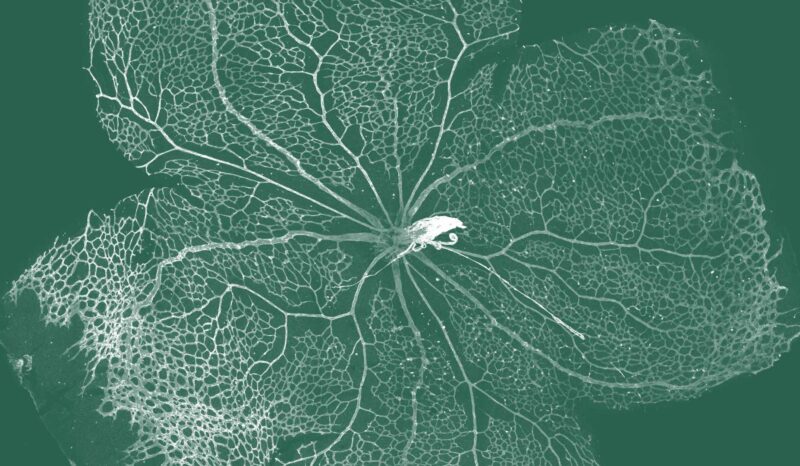

Recently, some ‘monoclonal antibody’ treatments have been shown to be effective for treating bowel cancer. These contain antibodies that bind to proteins that are helping the bowel cancer to grow. This blocks the proteins’ function, preventing cancer growth. Monoclonal antibody treatments are sometimes combined with chemotherapy to increase their effect.

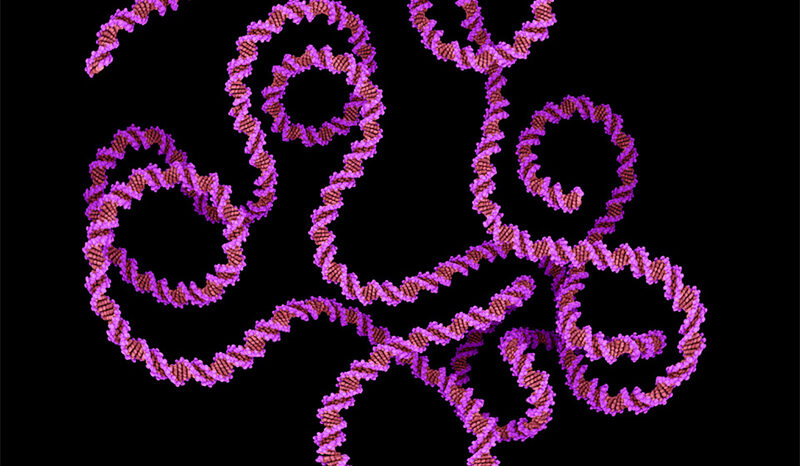

Bowel cancer treatment is currently hindered by a poor understanding of which patients will respond to which treatments. Genetic testing of bowel cancers is starting to reveal certain gene changes that predict whether a patient will respond well to a certain type of treatment. In particular, this testing can indicate whether monoclonal antibody treatments will be effective.

For more detailed information about bowel cancer treatment, please visit Bowel Cancer Australia.

WEHI researchers are not able to provide specific medical advice specific to individuals. If you have bowel cancer and wish to find out more information about clinical trials, please visit Australian Cancer Trials or the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, or consult your medical specialist.