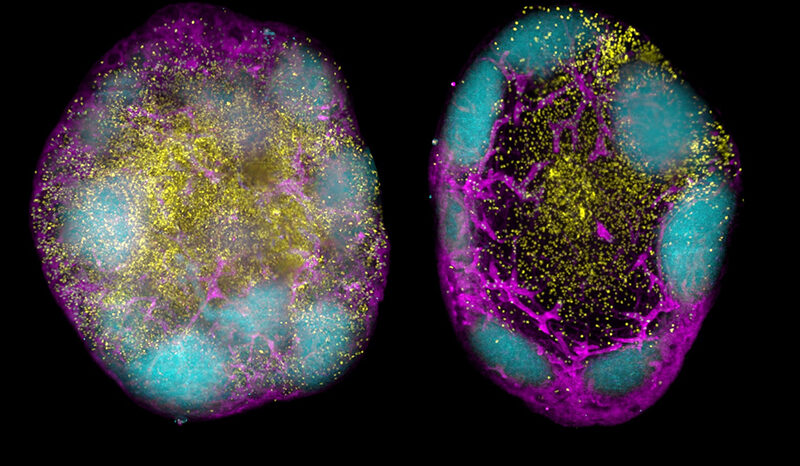

Joint senior author, Dr John Scott from MIPS, describes the signalling activity as “a balancing act within our cells.”

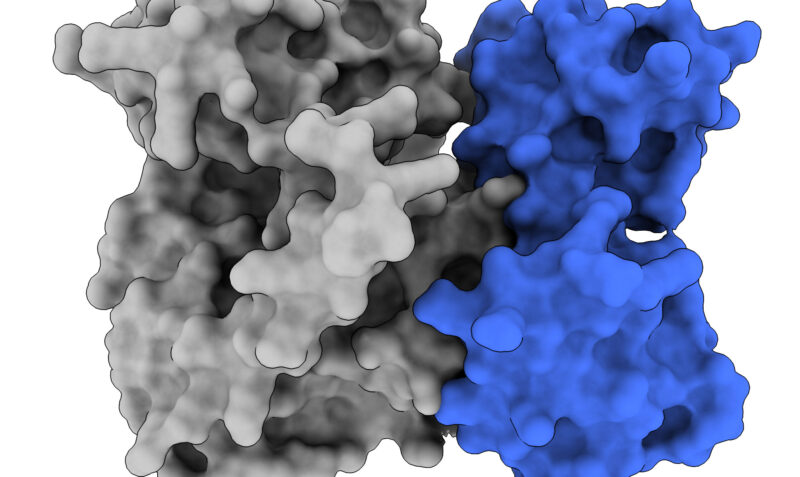

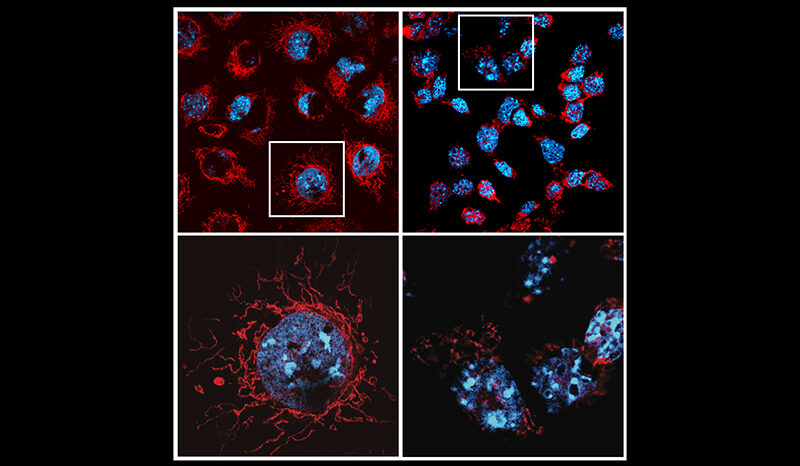

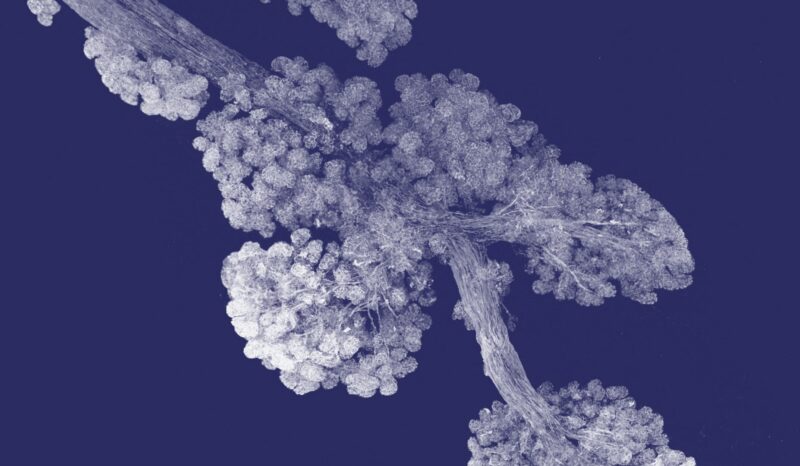

“Tumours form because cells ignore normal signals that tell them it’s time to stop growing, or that it’s time to die. When a signalling protein, such as PSKH1, interacts with certain proteins on a cell surface, this binding triggers a chain of events that can amplify the cell activity and lead to the formation of tumours,” Dr Scott said.

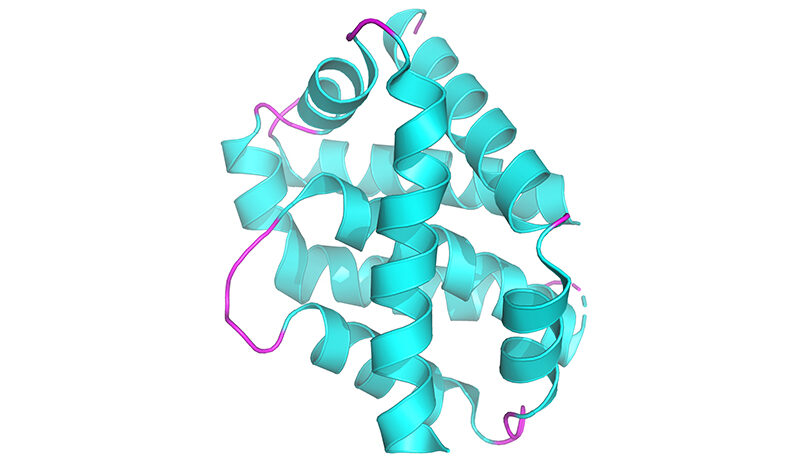

“Now that we know more about the proteins driving the “on” and “off” status of PSKH1, we can start to develop new drugs that target this molecule and, ultimately, improve therapies for prostate and other cancers.”

In 2024, prostate cancer was estimated to be the most commonly diagnosed cancer for males and for Australia overall. Treatments such as hormone therapy and chemotherapy can be effective, yet the side effects can be debilitating.

Joint senior author, WEHI deputy director Professor James Murphy, said the teams’ goal is to harness this new information to develop better, more targeted therapeutic approaches.

“Switching off PSKH1 essentially means being able to stop the progression of implicated cancers in their track, and thereby this new information opens up a whole new world of potential when it comes to developing new drugs,” Professor Murphy said.

Lead author Dr Chris Horne from WEHI said that understanding the mechanisms of how to switch PSKH1 on and off can also be applied to other molecules within the same family, which broadens the potential of the study’s findings to other cancers and disease.

“From here, our goal is to explore how we can start to develop new, effective therapies for signalling proteins, such as PSKH1, with fewer side effects,” said Dr Horne.