If you pull at the threads of many of the defining stories accumulated within the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute over the past century, pretty soon you encounter a tangle of professional and personal relationships. Tease at those a little more and you find the context in which – to use a most unscientific term – magic happens.

Professor David Hill can provide insight into a couple of the richest of those relationships, including one that nurtured the institute’s most profound research endeavour over some 60 years.

Keogh, Burnet and Metcalf, the beginning of a long friendship

Hill retired as director of Cancer Council Victoria (formerly the Anti-Cancer Council) in 2011, having worked there for 44 years. He was recruited to the council by director Dr EV (Bill) Keogh.

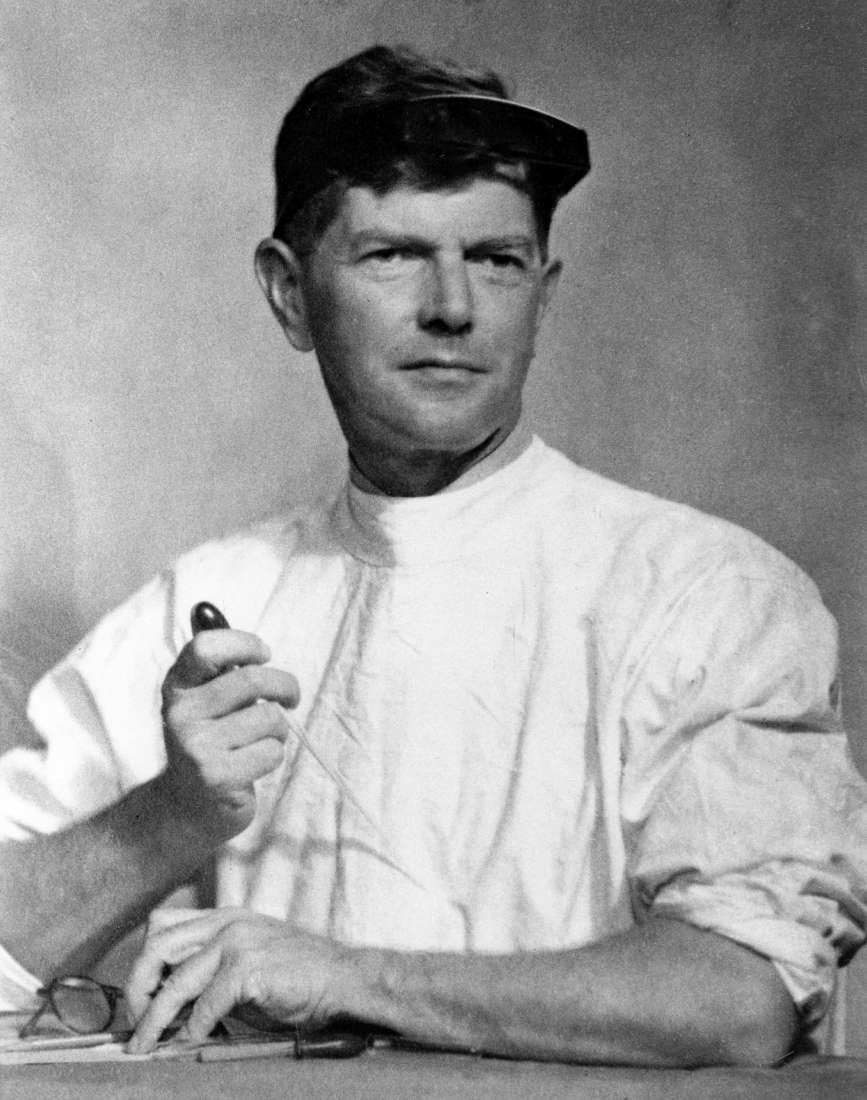

Keogh had been a researcher at the institute in the 1930s, where he collaborated with and befriended a young Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet before joining the Army’s medical corps in World War II – his second war, having served as a stretcher-bearer at Gallipoli. In the 1950s he was a mentor to a number of promising young talents. Hill was one of them, and a young University of Sydney medical graduate, Don Metcalf, was another.

Hill recalls that Keogh recruited Metcalf to Melbourne in 1954, offering him the Carden Fellowship to pursue the then challenging field of cancer research. He prevailed on “his collegial relationship with Burnet to get him placed at the institute”, Hill recounts.

Years later Metcalf recalled that at the outset of his work his new boss – who would win the Nobel Prize a few years later – informed him that cancer was an “inevitable disease” and that anyone trying to research it was “either a fool or a rogue”.

Metcalf was not dissuaded. Burnet famously consigned him to work in a small laboratory on a mezzanine above the institute’s research animal house. Hill recalls that “when I had occasion to visit him, it was a pretty stinky sort of place”.

Cancer Council underwrites Metcalf’s watershed discovery

I became quite aware, through Bill Keogh being my boss, and subsequently Nigel Gray being my boss, that the Cancer Council had a very special relationship with Don,” says Hill. “The Council in fact paid his salary until the day he retired, and that was only a few weeks before he died.

“When I became the director of the Cancer Council, I could see that Don Metcalf was still listed on our payroll. We had this quaint sort of biannual performance review, which Don took quite seriously. I – and Nigel Gray before me – would go up to the institute and we would sit in the director’s office and have a cup of tea with Don.

“Then I would go back to our board and say ‘Professor Metcalf is doing brilliantly, and we want to renew the arrangement.”

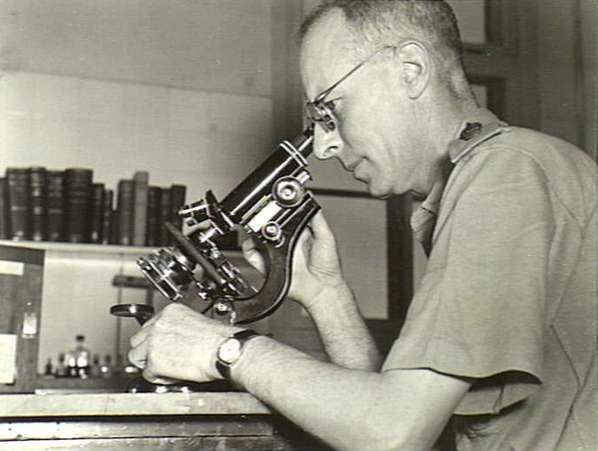

This enduring relationship would establish Metcalf as “the father of modern haematology”, underwriting his watershed discovery of colony stimulating factors (CSFs), which stimulate the production of white blood cells. The work at the institute enabled production of CSFs in drug therapies that have since benefited more than 20 million cancer patients.

The breakthrough took 15 years to come, and was never guaranteed. “In the early years Don was labouring incredibly hard, and he really was not showing much outcome,” says Hill. “He had to have tremendous persistence and belief in what he was doing. But so did the Cancer Council, and so did the institute.”

Match-making projects with benefactors

By 1965 a young immunologist trained by Burnet, Professor Gus Nossal, had become his handpicked successor as the institute director, and provided Metcalf support that would endure throughout his 34 years at the helm. Metcalf officially retired in the same year as Nossal passed the directorship to another institute talent, Suzanne Cory, but he kept working until December 2014.

Could the next potential Metcalf gain similar consistent, long haul support today? Hill doubts it. Even the most talented researchers reapply for their jobs and funding every few years.

That said, the collaboration of the Cancer Council and the institute has produced another defining research legacy.

“When I was on the National Health and Medical Research Council, I travelled often with Nic Nicola, and we talked about creative ways the Council might fund research.”

The established government funding structures – not inappropriately – are geared to safer research lines, prospects with a good chance of producing knowledge. “But perhaps it won’t be game-changing knowledge,” Hill explains.

“Drawing on insights from Nic, I initiated a scheme at the Cancer Council we called Venture Grants.” These supported high-risk but potentially high-gain research by match-making unfunded projects with high-worth benefactors. These are people “who want to be sure they are giving money for projects that wouldn’t have happened otherwise”.

This was an innovative approach to research funding, and was considered sufficiently interesting to be published in Science. At the institute, it has supported work including the successful pioneering programs such as the breast cancer laboratory headed by Professors Jane Visvader and Geoff Lindeman.

Productivity and impact in the field

Through the prism of his Cancer Council relationship with Metcalf, “I formed a view of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute as an institution,” says Hill. “I’ve had lots to do with various institutions, and I think the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute is exemplary. It has a wonderful culture, and I think that explains a lot of its productivity and impact in the field. The outcomes speak for themselves.

It’s an organisation that cares for its people, and the people care for each other. I think they are competitive in the best sense with other institutions, and their professional standards are very high.

It also possesses a “generosity of spirit that is not very common”, he adds, illustrating with the story of how every year the institute board would return to the Cancer Council a proportion of the royalty money generated by Metcalf’s CSF discovery. This in turn was cycled back into other cancer research programs. “There is no written agreement, nor any real convention, that required this.”