Within the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in the 1920s and 1930s is a small cohort of scientists who had served in World War I as young men, the experience profoundly shaping their professional and personal ambitions. A handful of them would find themselves back in uniform for World War II.

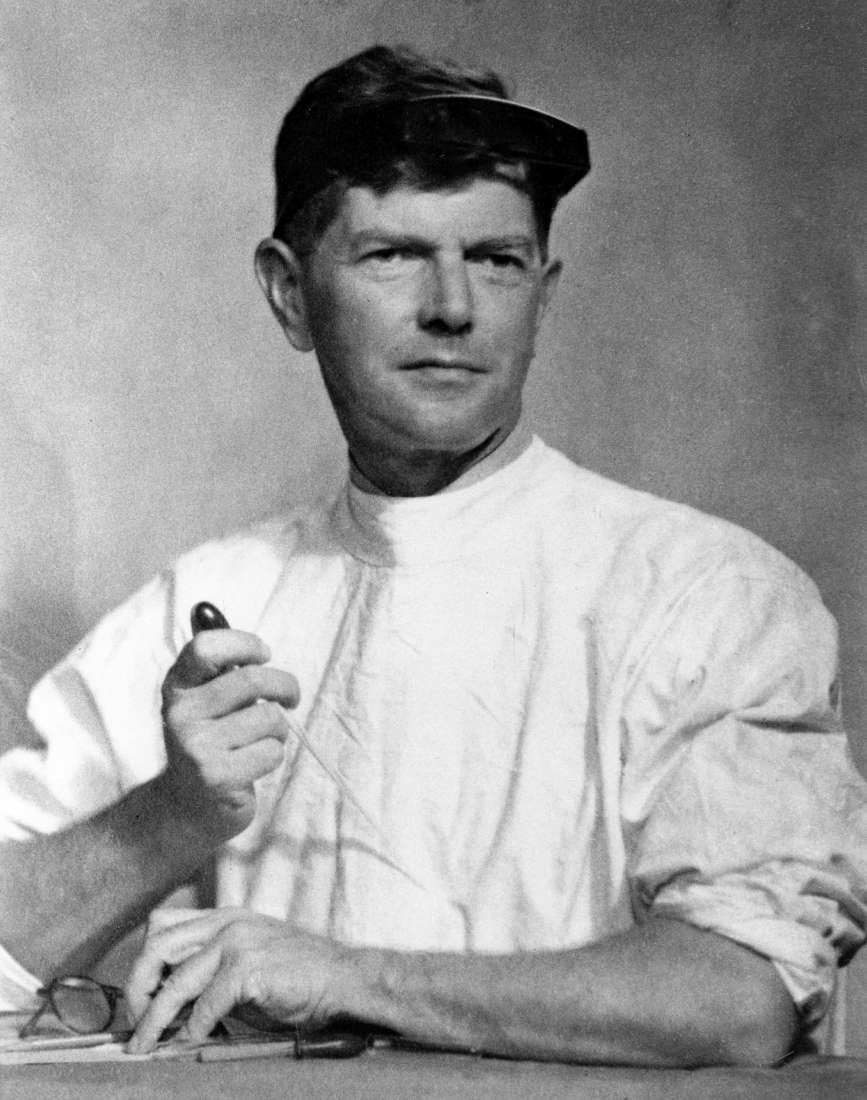

Most notably and famously they included institute director Sir Charles Kellaway, and his collaborator Sir Neil Hamilton Fairley, whose antimalarial work would have a profound impact on the course of the Pacific war.

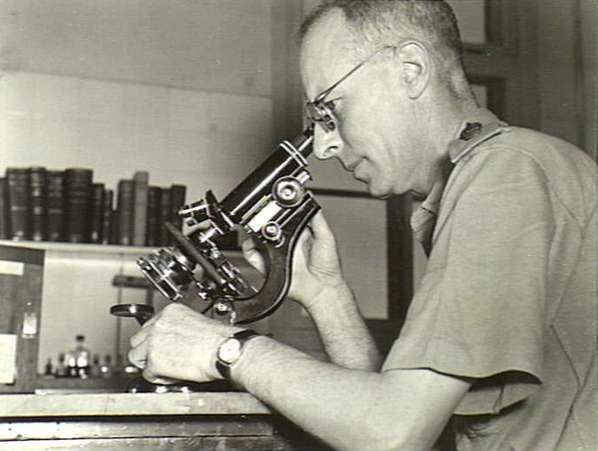

The story of EV Keogh

Another was Dr EV ‘Bill’ Keogh, a modest man who had wide medical influence over a long career but little public profile, probably because that’s how he liked it. He was perhaps best known for public health advocacy as medical advisor to the Anti-Cancer Council, a role he held from 1955 to 1968.

Keogh’s quietly extraordinary life is summarized in the title given to his story by his biographer: ‘Soldier, Scientist and Administrator’. Born in Malvern in 1895, one of four children raised by his mother after their father left, he enlisted in 1914 at age 19 and went to Egypt with the 3rd Light Horse Field Ambulance. He was a stretcher-bearer at Gallipoli and later a machine gunner on the Western Front, and was twice decorated.

Building a post-war life in research

After the war, about which he rarely spoke, he was “emotionally and nervously drained”, his biographer Lyndsay Gardiner wrote, and drifted for several years before beginning a medical degree at the University of Melbourne in 1922. He set his sights on a career in medical research, joining the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories in Parkville to begin a bench apprenticeship as a pathologist in 1928.

Keogh at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

In 1935 he was seconded to the institute to work on viruses, developing a strong friendship with fellow veteran and director Charles Kellaway. The virus work he did through that period led to a flurry of 18 published papers in the following years, two in collaboration with then deputy director Macfarlane Burnet.

Though their paths did not cross long within the institute, with Keogh returning to his CSL unit by 1937, the friendship with Burnet endured. Their brief collaboration spurred “an association with the institute that was a tremendous support to me on many occasions in the next 30 years”, Burnet wrote. Not long before his death in 1970 Keogh read and reviewed the manuscript of Burnet’s history of the institute, and is recognized in the acknowledgements for his assistance.

Veterans and medical research in World War II

When World War II war broke out medical research was put on a war footing. Kellaway was appointed director of pathology at Army Headquarters in Melbourne, a role later taken over by then Colonel Keogh. In this war Keogh would work with Brigadier Fairley to overcome the catastrophic malaria and dysentery outbreaks devastating troops serving in New Guinea and the wider Pacific.

Post-war research

After the war Keogh played significant roles in infectious disease, coordinating Victoria’s efforts to tackle tuberculosis, and liaising again with Burnet and with Professor Jonas Salk at the University of Pittsburgh who, in 1950, had discovered a vaccine for poliomyelitis.

Keogh had a key role in facilitating the production and roll-out of the vaccine in Australia from 1956. Polio cases dropped to virtually zero within a few years.

Keogh as mentor

After Keogh’s death it was observed in remembrances of him that perhaps his greatest achievement in medicine was to “to discern and nurture qualities in others and help them achieve to the limit of their ability”1.

In this regard his standout legacy was in identifying and supporting the talent of a young Don Metcalf back in 1956. Metcalf was a new recruit from Sydney, already keenly interested in cancer research, and “from the beginning was sponsored by Dr E.V. Keogh who, throughout most of my time at the institute, had a special position that combined the qualities of a guardian angel and a grey eminence,” Burnet wrote in 19712.

“Keogh was impressed with Metcalf and, having just become medical director of the Anti-Cancer Council, he arranged for that body to support Metcalf for at least two years.” It continued to support Metcalf’s work through the Carden Fellowship until his retirement in December 2014, underwriting some of the most significant cancer research of the age.

Metcalf’s discovery of colony-stimulating factors (CSFs) is estimated to have benefited more than 20 million cancer patients worldwide.

Keogh died of cancer in September 1970. In March that year he struggled the distance of the anti-Vietnam War Moratorium March. He left his body to the anatomy department, University of Melbourne.

1 Cancer Council Victoria, Dr EV Bill Keogh. Available from http://www.cancervic.org.au/research/researchers/dr-bill-keogh.html. Accessed June 2015.

2 Burnet, F (1971)