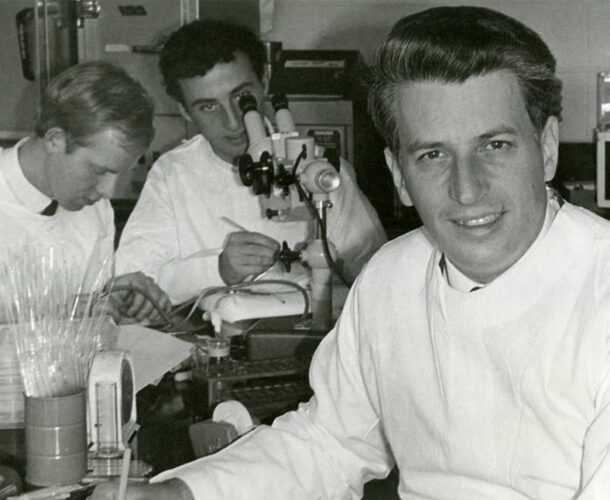

Sir Gustav Nossal, now one of Australia’s most distinguished and revered scientists, begins his research career at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

The accidental immunologist

As a young scientist, Nossal wanted to study viruses, not the immune system. “They were the simplest forms of life,” he recalls now of this youthful flirtation. “I thought if I could understand how a virus multiplied, I could unravel one of the secrets of life.”

So, after graduating in medicine in Sydney, he came to Melbourne to work with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research and its internationally renowned head, Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet. “Little did I realise that Burnet was on the brink of turning the institute from virology to immunology,” Nossal recalls. “It was a big shock to me, and it was also a disappointment.

“But I also didn’t realise that I was in the presence of genius. What Burnet had done was identify a wave that was about to break. Those very same systems that allow vaccines to protect us against disease can turn traitorous and give us autoimmune diseases. I had also failed to focus on the fact that the immune system was the only barrier to organ transplants.”

Advancing immunology

Nossal swallowed his disappointment and offered to work on one of Burnet’s immunology theories. This resulted in him making a scientific discovery about cell antibodies – each cell produces only one type of antibody – that jetted him to world-wide prominence at the ripe old age of 27.

A new leader for the institute

A few years later, when Burnet retired in 1965, Nossal was promoted to the role of director. He held this post for 35 years, and under his leadership a restructured institute made many important medical discoveries, cementing its international renown for scientific prowess.

Nossal himself is renowned for being charming, genial and expansive, and he turned those qualities to good use. Realising that the institute would fall behind if it failed to keep up with the technological revolution, he worked hard – and successfully – to cajole governments and philanthropists into donating to equipment and a new building for the institute.

Identifying the best and brightest

He also made several key scientific appointments that led to major discoveries.

He hired immunologist Jacques Miller, “the living person who most deserves a Nobel Prize but never got it”, Nossal says.

“He was the person who discovered the function of the thymus. The thymus was seen as an evolutionary relic; in fact, it is the mastermind organ of the immune response, the conductor of the immunological orchestra. That was a great breakthrough.”

Setting up the CSFs story

The second crucial move, he says, was that “I brought Professor Don Metcalf in from the cold. He was working in a shabby annexe and I brought him into the inner fold and made him deputy”.

Metcalf is now known as “the father of modern haematology” for his discovery of colony stimulating factors (CSFs). They are used to stimulate the production of stem cells in the bone marrow, an activity that is suppressed by conventional cancer chemotherapy. CSFs have been given to 20 million cancer patients around the world to prevent them developing infections from immune suppression and lowered white blood cell counts after chemotherapy.

CSFs also revolutionised transplant medicine, leading to simpler techniques to perform bone marrow transplants for patients with blood diseases such as leukaemia.

A champion for global health initiatives

In 1990, Nossal was honored with the Albert Einstein World Award for Science and in 2000 he was named Australian of the Year. In 1996, however, he was faced with a dilemma: he had turned 65 and had to retire as director of the institute. “What the hell was I going to do?” he wondered.

He had links to the World Health Organisation and decided to devote himself to advocacy for international public health: “I made my night job into a day job.”

Then, in 1998, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Children’s Vaccine Program offered him the role of chairman of its Strategic Advisory Council, which included assessing grant requests – “Peering into the future of research: what areas are the most promising for tomorrow?”

A lifelong passion

Now 83 and an emeritus professor at the University of Melbourne, Sir Gus looks back on his past at the institute with “an overwhelming sense of having been unbelievably lucky. Who actually gets paid for doing what they passionately love? Who has the freedom a scientist has to follow his stars?”