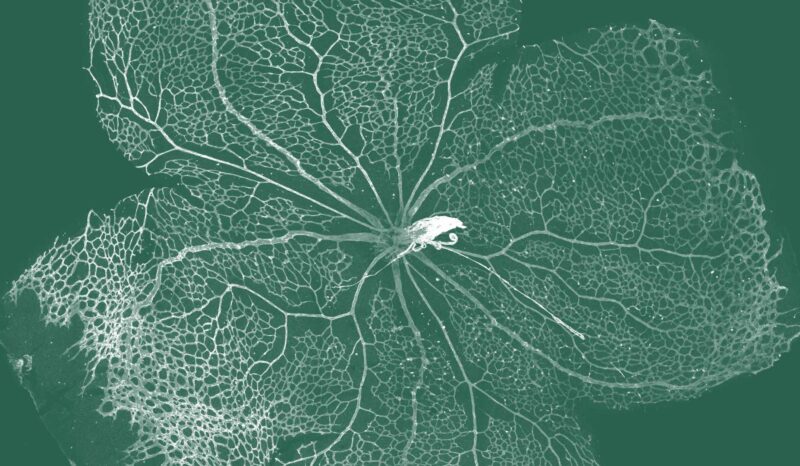

The growth of cells and tissues in the body is under tight control. This allows the body’s systems to work together. Sometimes it is important for certain cells or tissues to grow more than others. Examples of this are during the growth of a child, and the regrowth of tissue after an injury. There are many genes and proteins in cells that regulate cell growth in response to appropriate signals.

Cancer is initiated by a cell dividing uncontrollably. This is caused by changes to the genetic material (DNA) of the cell that alter the normal growth control genes and proteins. Cancer development is usually triggered after a single cell has acquired several changes that work together to drive cancer formation. Cancer cells typically contain higher-than-normal amounts of proteins that promote cancer growth. They also lack certain proteins that, in normal cells, limit growth.

Usually cancer-causing changes occur by chance (spontaneously). In some cases, cancer-causing genetic alterations are inherited from parents. Cancer-causing viruses can also introduce cancer-causing changes to cells. For example, the human papilloma virus (HPV) changes the DNA of cells in a woman’s cervix, which can lead to cervical cancer.

You can read more about the genes that are linked to cancer in our cancer page.