Anaemia affects over 1.5 billion people around the world, including about 1 in 20 Australians.

It occurs when a person lacks oxygen-carrying red blood cells (haemoglobin) and iron.

The blood disorder is a major public health concern that mainly affects low and middle-income countries, where the condition remains one of the most avoidable causes of illness and death.

While symptoms commonly include severe fatigue and shortness of breath, if left untreated, the condition can also cause heart problems, pregnancy complications and even death.

In 2014, WEHI researchers began a study at the request of the WHO, to formally review its global anaemia guidelines that were last updated in 1968.

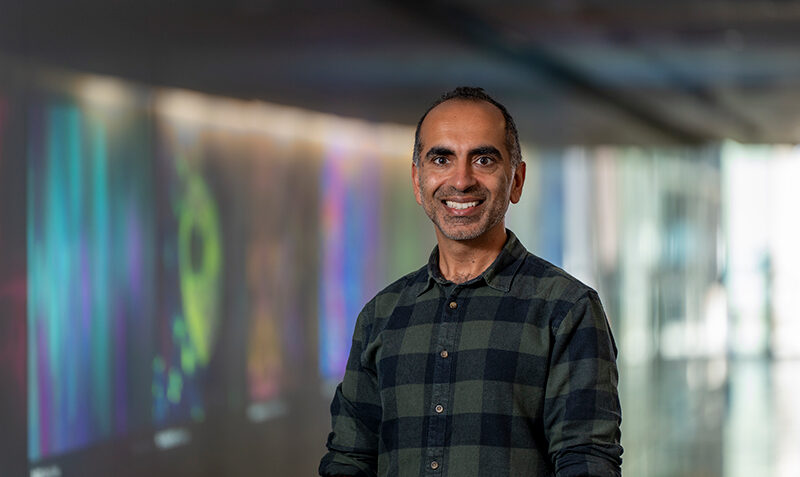

Study lead and Acting WEHI Deputy Director, Professor Sant-Rayn Pasricha, said while anaemia can be diagnosed by measuring the amount of haemoglobin in the blood, there is currently no consensus on the thresholds that should be used to define the condition.

“Currently, a patient can be diagnosed with anaemia at one clinic but not the other – even within the same city,” Prof Pasricha, also a haematologist and the Head of WEHI’s Anaemia Research Lab, said.

“As people living with anaemia often need ongoing treatment, every anaemia misdiagnosis causes unnecessary costs and pain.

“While the WHO guidelines are a key resource for health professionals in treating anaemia, experts also depend on other sources like medical textbooks and leading medical societies to guide patient treatment – but these resources can have varying information.”

The revised WHO guidelines help to alleviate this critical challenge by providing a clear set of haemoglobin thresholds that could, for the first time, be uniformly used to harmonise the diagnosis and treatment of anaemia for billions of people worldwide.

“We hope these new guidelines will be adopted as the new global advice and help to reduce the health burden that continues to be inflicted by anaemia across the world,” Prof Pasricha said.