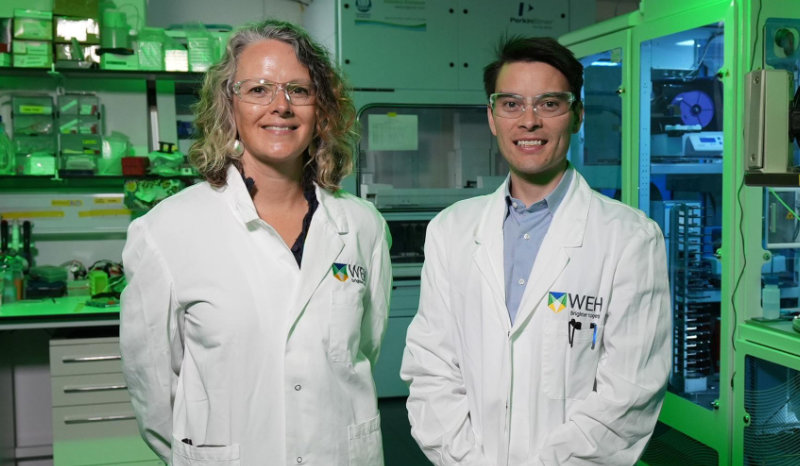

Rebecca:

I’m a biostatistician working in WEHI’s Population Health and Immunity division providing statistical, analysis and design support on clinical research being conducted in Malawi.

I stumbled on the idea of becoming a biostatistician while completing my PhD, studying psychology and statistics. My supervisor said, “you know, you could do this as a job,” and it opened up a whole new world for me.

I like working in global and public health, knowing that even just the slightest change can transform somebody’s whole life. I love that the numbers I’m crunching tell a story that will help at least one family’s birth outcome, and hopefully then a whole community.

I suppose I’ve got a head for numbers and a heart for people, and it has led me to working with Glory, helping women in one of the world’s lowest income countries overcome iron deficiency.

Our study, the first of its kind, found that a single iron infusion could significantly reduce anaemia in pregnant women, compared with daily tablets.

The finding paves the way for more effective health policies to reduce the global health burden of anaemia, which remains one of the most avoidable causes of illness and death in resource-poor nations like Malawi.

Globally, anaemia affects 42% of children under five years and 40% of pregnant women.

In this partnership, I oversaw the large dataset and the analysis, and Glory led the field work and solved problems on the ground. With Glory’s support the field team interviewed over 21,000 Malawian women to find the 862 women for the trial. This impressive undertaking is a credit to her and the team.

Glory and her team created the grassroots momentum for the trial that was previously thought impossible in a complex resource limited setting. They visited churches, schools, health clinics, organised football matches and even took a megaphone to marketplaces to raise awareness.

She personally talked to women about how a single iron infusion could help them – with fatigue, wellbeing and newborn health.

Thanks to Glory, and her determination to change the future for Malawian women and families, the findings will open a whole new field of research and potentially transform health policies for communities worldwide.

Glory:

When I was a child, I knew I wanted to become a doctor. But when I graduated and started working, I saw so many children and pregnant women with cases that I felt could be easily prevented.

One day I turned around and said, “I think I’m going to do preventive medicine.” I felt that early public health interventions could improve health and take the pressure off an already resource constrained health system.

After completing my masters in epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, I joined Malawi’s Training and Research Unit of Excellence (TRUE) and then began collaborating with WEHI.

Anaemia is a major public health burden in countries like mine. It affects nearly half of all pregnancies in Africa, often leading to poor maternal and newborn outcomes and contributing to death.

Pregnant women with anaemia face higher chances of post-partum haemorrhage, stillbirth, post-natal depression and bonding issues with their newborn.

Even though the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends iron tablets twice daily for pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa, less than 30% of the population take this recommended dose.

The 15-minute infusion is quicker and easier than taking daily tablets. Apart from the fact that the infusion could treat anaemia immediately, most women were simply happy that they wouldn’t have to take pills on a daily basis or struggle with the side effects caused by the tablets.

While our people were equally ‘hungry’ for a solution, one of the drivers for the success of the trial was massive community engagement and awareness campaigns prior to and throughout the trial period. I spent time talking to community leaders, building rapport and engaging with women at community gatherings, especially since very few have phone or internet access.

After the completion of the trial, I was invited to WEHI to advance my skills in data analysis – an incredible opportunity given I am pursuing my PhD.

Working under the same roof as Rebecca meant that we could solve problems in minutes and carry on, rather than taking days across time zones. I was able to offer an ‘on the ground’ contextual perspective to Rebecca’s quantitative analysis. This added a deeper layer to the interpretation of the trial results.

It was a valuable exchange that we hope will ultimately drive policy change. In fact, our results were presented at a special WHO meeting to discuss how our findings might be turned into policy – something I’m very proud of.

If our findings create change for women and children everywhere, I’ll be a very happy epidemiologist!

–

Header image: Collaborating under the same roof meant that Glory Mzembe (left) and Dr Rebecca Harding (right) could reduce delays and share insights to deliver a deeper level of analysis for their anaemia study – the first of its kind worldwide.