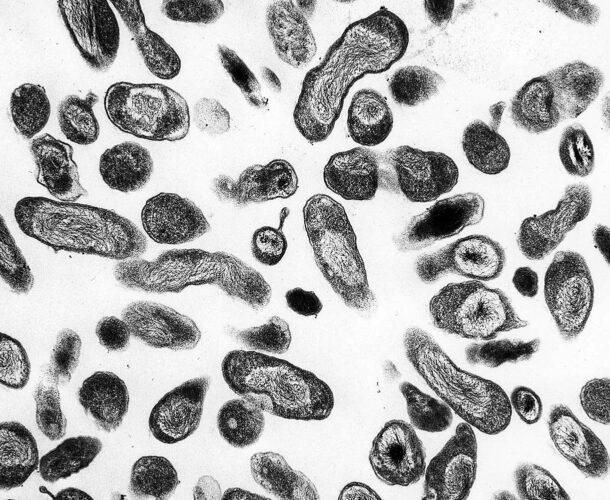

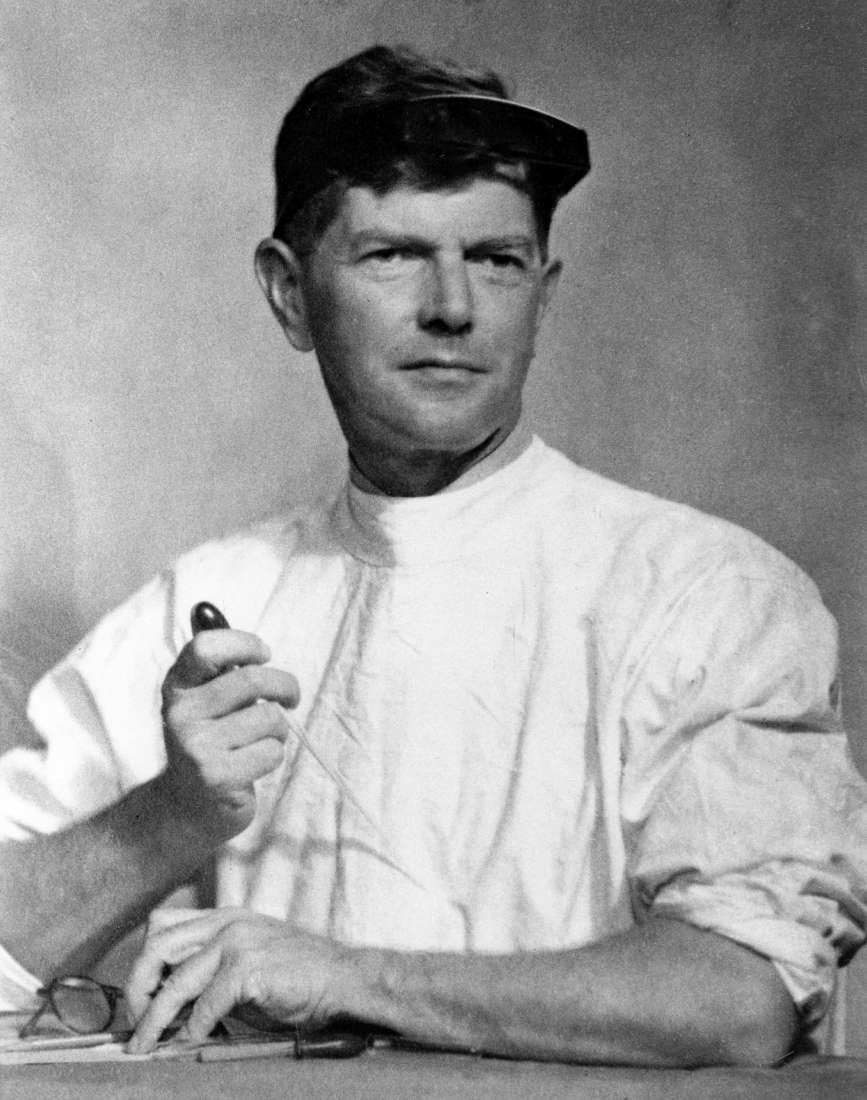

A year after returning to the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Professor Macfarlane Burnet is to enshrine his name and that of the institute in the annals of medical history with the discovery of the microbe named after him: Coxiella burnetii.

Coxiella burnetii is the agent that spreads Q fever or what was known as ‘abattoirs disease’.

Outbreak in abbatoir workers

Burnet’s work into Q fever is part of a collaboration with Dr Edward Derrick, then director of the Laboratory of Microbiology and Pathology at the Queensland Health Department. In 1935, Derrick becomes aware of an outbreak of disease among Brisbane abattoir workers, with symptoms resembling a lengthy attack of flu or a mild bout of typhoid. It can be fatal. He conducts experiments with animal models injected with the infected blood of patients and, after a year’s work, became the first person to identify Q fever as a distinct disease.

But while Derrick knows the condition is somehow contracted from animals going to slaughter, and that the infective agent of the fever is present in the spleen, he is unable to determine the micro-organism responsible or work out how it got to the abattoirs. Derrick, who had started his career as a laboratory investigator with a short stint at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in 1922, now turns to Burnet for help.

A rare discovery

Burnet, assisted by Mavis Freeman, has his breakthrough within weeks. Peering down the microscope at a section of infected tissue he notices a ‘vague herringbone pattern’ of tiny rods that ‘could be like a rickettsia (bacteria) or a ‘big’ virus like that of psittacosis’. ‘It was one of those rare discoveries which can be dated to the day and the minute’, he wrote in his autobiography, expressing the researchers’ ‘immense pleasure’ at the sight before them.

Derrick named the disease Q (for ‘query’) fever, wanting to avoid any offence caused by using the colloquial ‘abattoirs’ fever’ and any reference to Queensland, which might have adverse connotations for tourism. He was also responsible for naming the microbe Rickettsia burneti. Taxonomists later changed it to Coxiella burnetii after it was found not to be a Rickettsia.

Q fever spread

Burnet and his team continued their research into Q fever for the next two or three years, carrying out antibody tests for Derrick and comparing their Australian organisms with American examples of rickettsia. Derrick and his colleagues showed that the microbe was a natural infection of bandicoots, whose ticks transferred it to cattle. The cattle tick conveyed it from cow to cow. Interest in Q fever waned at the Institute with the beginning of World War II in 1939.

The joint effort that results in the recognition of Q fever as a distinct disease, the isolation and characterisation of the responsible microbe and the findings of the ways the disease could be transmitted rated as what Burnet later called the most important medical find in infectious disease in Australia. He also seemed to enjoy too, the distinction of becoming the first recorded laboratory worker to acquire the disease, in January 1937.