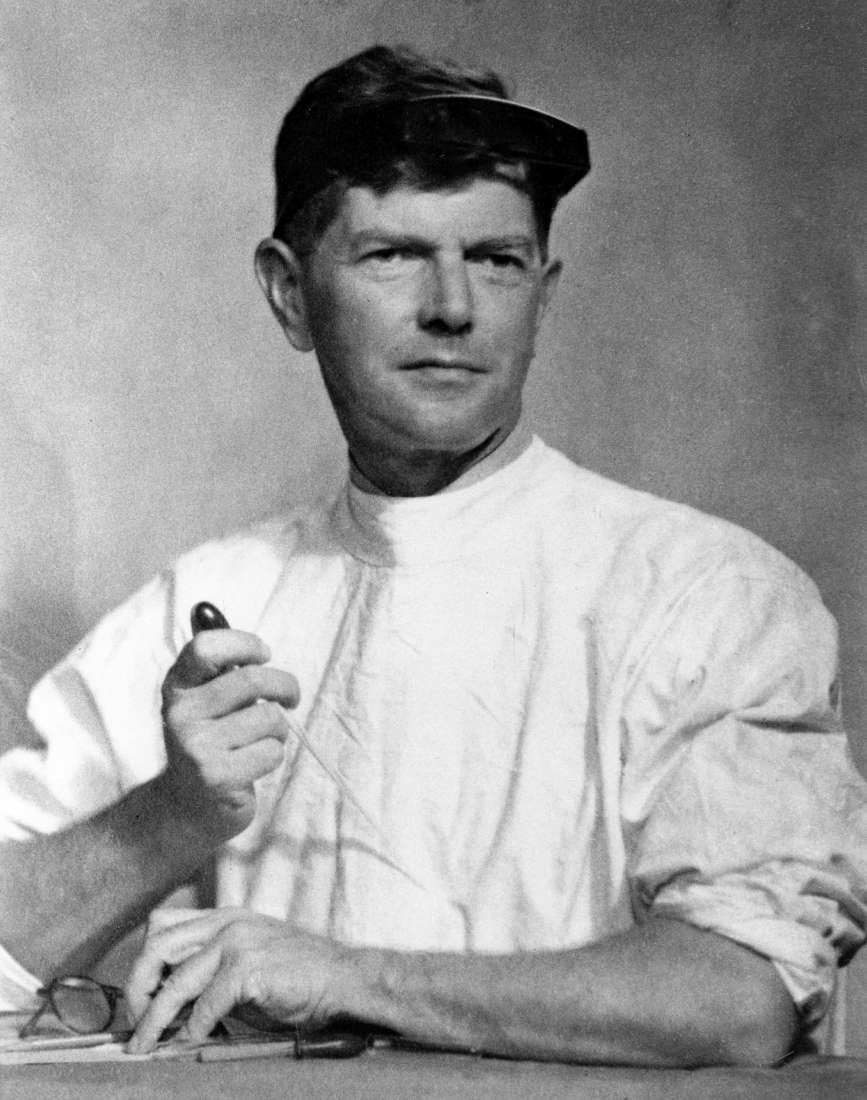

Upon returning to the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet takes up the directorship of the new virology department, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation.

A public health risk?

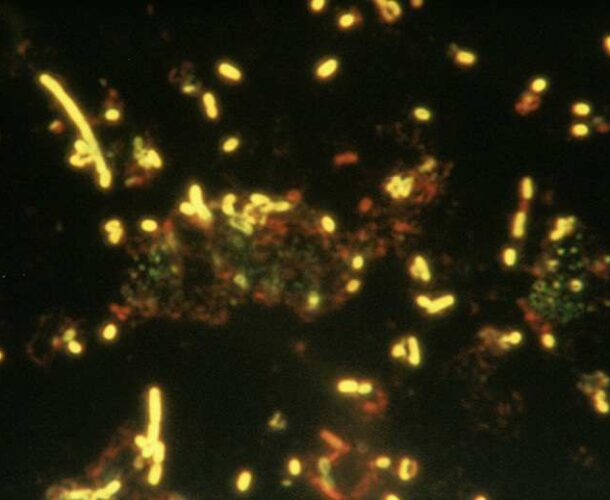

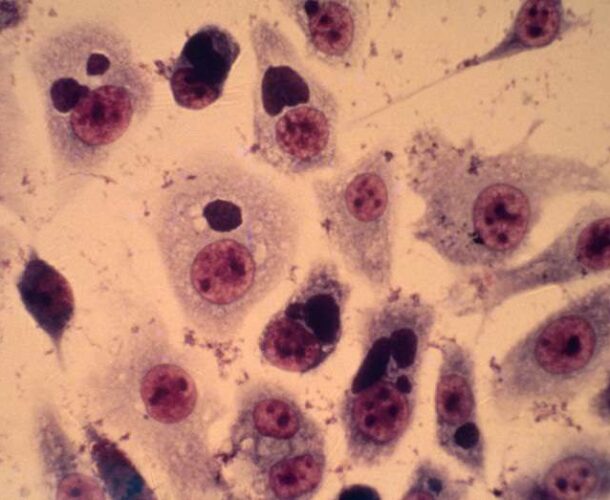

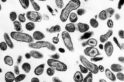

The department’s first task is to investigate the extent to which Australian parrots are infected by the psittacosis ‘virus’, (technically the bacterium Chlamydia psittaci), for the Commonwealth Director-General of Health, and to find out whether human cases are involved.

Psittacosis or ‘parrot fever’ is a lung infection mostly carried by birds of the parrot family. It can cause pneumonia and typhoid-like symptoms in humans, including fever, headaches, a dry cough, nosebleeds, shortness of breath and muscle aches, and can be fatal.

There had been a widespread epidemic of the disease in 1929-30 in the Americas and Europe, and a consignment of Australian parrots shipped to London arrived decimated by the disease.

The first birds Burnet and his team examined were a batch of wild grass parrots from northern Victoria received by a Melbourne dealer; about half are infected.

Healthy birds harbour disease

Burnet demonstrates that psittacosis is present in apparently healthy parrots obtained from other bird dealers. It becomes clear to him that the psittacosis agent was a natural parasite in all the common species of parrots and cockatoos, including budgerigars. A study published by Burnet in 1935 shows that asymptomatic psittacosis among parrots in the wild could cause the disease to erupt when the birds experienced the stress of being confined.

The researchers tracked down human cases too. Dr Jean Macnamara, then working as a part-time field worker in the department, traces one small group of ill people to a batch of young cockatoos taken from nesting holes in the wild several weeks previously and kept in filthy surroundings in a Melbourne suburb.

They find that young birds are particularly vulnerable, as are what they call ‘older people’, with a number of fatalities of people over forty.

Burnet’s ‘public service announcement’

Burnet took his duty to warn people about the dangers of contracting psittacosis to heart.

So much so that when Sir John Medley, the new vice-chancellor of The University of Melbourne and therefore an institute board member, visits his lab unexpectedly with Professor Charles Kellaway one day, Burnet warns both men that ‘since they were over forty, they should remain at the door and not approach the bench’. Burnet, at the time surrounded by a team busily working on the brightly coloured corpses of lorikeets and rosellas, wasn’t sure whether Medley thought him impertinent or was grateful for the advice.

He warned public health authorities about the potential danger to people of the trade in young cockatoos and other parrots, but eventually agreed with them that the risk to the public was too small to warrant its ban.