One of the earliest appointments to the institute, Dr (later Brigadier Sir) Neil Hamilton Fairley brings great expertise in parasitology and tropical illnesses.

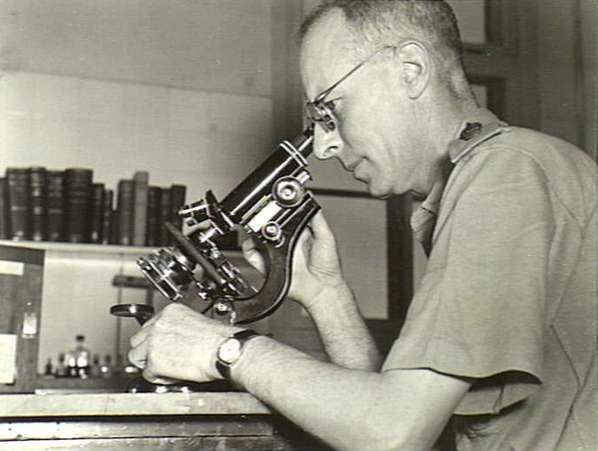

Sir Neil Hamilton Fairley

Remembered as one of the greatest names in Australian medicine, Fairley spent only a few years of his distinguished career in the laboratories of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. He nonetheless left a mighty and enduring legacy of influence on its program and character.

Early life

Fairley was born in Inglewood, a small town in gold country north of Bendigo, one of four brothers who all became doctors. He graduated as dux from Scotch College and went on to study medicine at the University of Melbourne.

World War I and crucial connections

Qualifying during World War I, Fairley enlisted in 1916 and was dispatched to the Middle East as a pathologist, forging links and friendships with a cohort of military medicos whose inter-relationships would one way or other shape the Hall Institute over the next decades.

They included Charles Kellaway, who would become the institute’s director, and (Sir) Charles Martin, director of London’s Lister Institute of Preventative Medicine, who had previously worked in Sydney and Melbourne and was a mentor to both Fairley and Kellaway.

Fairley comes to the institute

After two years working with Martin in London, along the way qualifying in tropical medicine, in 1920 Fairley joined the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute as first assistant under director Dr Sydney Patterson, and began research on syphilis and hydatid diseases.

In that period he had a profound influence on a young Frank Macfarlane Burnet, whose earliest memories of the Hall Institute recall Fairley’s attempts to treat patients with typhoid fever by intravenous injection of typhoid vaccine. “In all probability it was this interest in Fairley’s work that mapped out the general course of my own research, which started with two papers on the antibody response in typhoid fever and moved directly to the bacteriophages active against typhoid and similar intestinal bacteria,” Burnet wrote.1

Snake bites and antivenoms

Fairley left Melbourne late in 1921 to take up a position in Bombay to pursue his interest in tropical medicine. He went from there to another stint in London before being recruited back to the Hall Institute by Kellaway.

Fairley persuaded Kellaway that the institute should revisit the promising snake bite antivenom research that Charles Martin had pursued in Sydney 30 years earlier. While fatal bites were relatively rare – killing maybe dozens of people a year – “it is an accepted imperative that a civilized country should have stored in strategic locations antivenenes which can deal with the bite of at least the most common venomous snakes of the region”, Burnet observed in his history of the first 50 years of the Hall Institute.

“Nothing of the sort was available in 1928, and when Neil Fairley returned to the institute after a sojourn in India, he was very conscious of the deficiency.”

A major research program commences

Kellaway’s successful submission to the Federal Government for a grant to pursue the work was the first such funding secured by the institute, and the template for the grants program which endures to this day under the National Health and Medical Research Council.

It also brought the young institute powerfully into public consciousness, playing to the fear and fascination around snakes. “Basic to anything else that may be undertaken is the collection and storage of venom,” as Burnet explained. “Here the recipe begins, first catch your snake, then milk it.”

Fairley persuaded the Melbourne Zoo and a collection of snake wranglers to assemble the facilities and reptiles required sustain the research. He was, Burnet said, “always a man to get things done without delay and as he wanted them.

Australia’s first commercially available snakebite antivenom

“The work in the 1928-43 period, led by Fairley and Kellaway, brought knowledge of Australian snakes and snake venoms up to and a little above the current level in most other countries where snake-bite was a practical problem,” Burnet wrote. “It led to the production of antivenene which was subsequently shown to be effective against both tiger snake and copperhead – though it must be confessed that most of the occasions for its effective use in those days were in laboratories concerned with research or in amusement parks.”

Wartime and tropical medicine

In 1929 Fairley departed Melbourne for private practice in London and teaching in tropical health. With the outbreak of World War II he returned to the Australian military, providing medical advice on diseases such as dysentery and malaria first in the Middle East and later in the Pacific, where they were taking a terrible toll on allied troops.

By then Brigadier Fairley, he persuaded US General Douglas Macarthur that disease control would be critical to the war effort. He recruited hundreds of volunteers to trial potential antimalarials, identifying the new drug atebrin as protective.

“The findings, recorded in great detail, have never been challenged, and provide unique information, unobtainable under any conditions except those of a major war,” observed Frank Fenner (another Walter and Eliza Hall Institute alumnus and wartime malaria specialist) in his 1996 Australian Dictionary of Biography entry on Fairley.2

Although there were some limitations to the usefulness of the drug, its use by troops saw a dramatic fall in malaria cases, defining a turning point in the Pacific campaign.

After the war Fairley returned to practice in London, but became seriously ill himself in 1949, and never fully recovered. He died in 1966.