The institute embarks on a major study of animal venoms. In collaboration with the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL), the team produces Australia’s first commercially available tiger snake antivenom.

Spider, mussel, bee and even platypus toxins are also studied, revealing insights into human physiology, particularly in relation to immunology and inflammatory conditions.

Dangerous work

The research team requires large volumes of snake venom to investigate how venoms act, how the effects of snakebite can be mitigated, and to develop serum with antivenom properties.

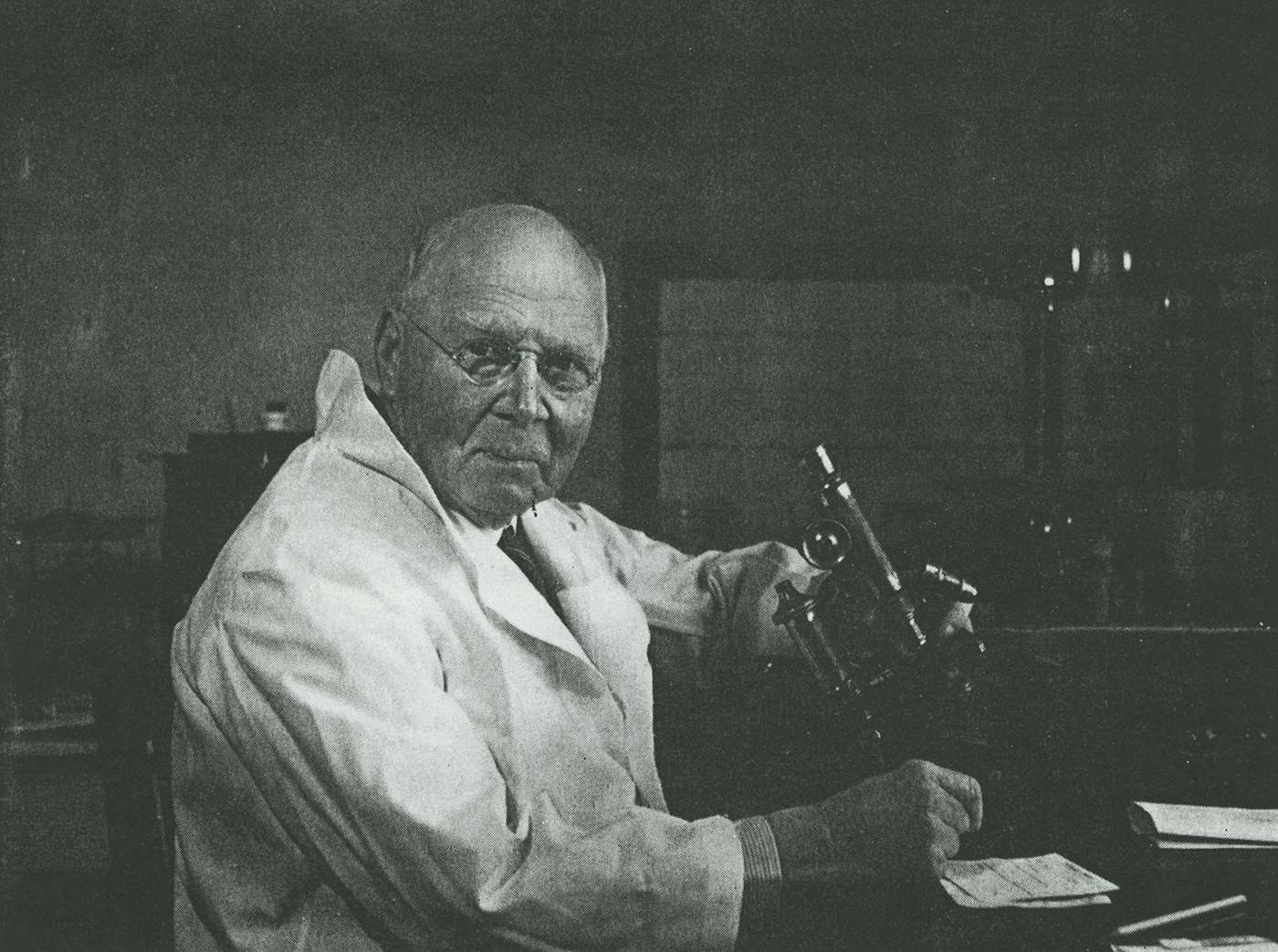

The Melbourne Zoo provides snake facilities and handlers, and institute staff undertake a hazardous program of venom collection. Director Sir Charles Kellaway is among the first beneficiaries of the new antivenom, after being accidentally bitten by a tiger snake in the course of his research.

Outcomes

The collaboration leads to direct therapeutic benefits for many Australians.

The research also has broader significance. It underpins the first federal funding for medical research, cements Kellaway’s scientific reputation, and leads to the identification of a slow reacting substance of anaphylaxis, SRS-A, which would have substantial impact decades later.

Background to the institute’s antivenom research program

In 1927, the decision to develop snakebite antivenom might have been construed as both a genius public relations strategy and an inspired bit of political lobbying.

Certainly it stirred public and media interest in the young institute, and it galvanised the model for federal funding of medical research that endures to this day. But it also delivered a life-saving therapy to the community. This noble ambition faced plenty of obstacles, but was also helped along the way by a series of opportune encounters.

Credit for the idea goes to Dr Neil Hamilton Fairley, “who had worked in India and had seen the Indians using snake antivenom”, says Ken Winkel, director of the Australian Venom Research Unit, 1999-2015.

Fairley was a tropical medicine specialist attached to the institute, who had spent five years in Bombay. On returning to Melbourne he persuaded Kellaway, to apply his expertise and that of his laboratories to antivenom research.

The groundwork had been laid 30 years earlier. Research by Dr Charles J Martin at Sydney University and then at the University of Melbourne over the 1890s, and by his collaborator Frank Tidswell of the NSW Department of Health, had produced a tiger snake antivenom which they had successfully tested in animals. But their project stalled for want of further research investment.

“There was no federal support, no funding vehicle to address this or other medical problems,” explains Winkel. Martin moved on to head the Lister Institute in London, and the antivenom work languished.

Upon receipt of one of the first Australian Government medical research grants, Fairley conducted epidemiological studies of the frequency and outcomes of snakebite in Australia. He concluded that while the data was patchy, the casualties were likely in the range of dozens a year. The program evaluated the efficacy of standard treatments – ligature and excision – and determined these were insufficient, that an antivenom was required.

Snakes in the laboratory

The program relied on acquiring large quantities of snake venom, which meant collecting, handling and milking venom from hundreds of deadly species. “The work caught the public imagination – the snake men, dicing with death,” says Dr Ken Winkel from the Australian Venom Research Unit at the University of Melbourne.

Winkle, a former institute PhD student, joined the unit in the mid-1990s, “I hadn’t kept snakes under the bed like many of the characters in the field, but I was broadly interested in the place where medicine meets nature.” The position offered the broad scope of science and engagement with industry, government, media, and community organisations. Winkel, now recognised as a leading toxinologist, remains in the unit today.

What he didn’t realize at the outset, but would come to understand as a student and chronicler of Australia’s history of venom research, was that he was stepping back into a formative, fascinating but largely forgotten chapter in the history of his alma mater, the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

The cover photograph of a book Winkel co-authored in 2013 – Venom: Fear, Fascination and Discovery – features a nonchalant Donald Thomson, an anthropologist and ornithologist who was recruited to the institute’s antivenom program, shown milking a taipan on Cape York.

“Kellaway was also milking snakes, and was bitten by a tiger snake and almost died of anaphylaxis,” says Winkel. He was saved by his own antivenom and the prompt attention of doctors at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

Later research benefits

By 1930 the tiger snake antivenom developed by the institute was being produced by CSL for clinical use. Kellaway’s interest shifted toward understanding the biological effects of venom, using it as a tool for understanding human physiology. He investigated this with colleagues including Fannie Williams, Henry Holden, Everton Trethewie and Wilhelm Feldberg.

The insights Feldberg, a refugee from Hitler’s Germany, brought to the institute gave Kellaway’s venom inquiries a significant second wind, says Winkel. The pair’s pioneering work using venoms to help identify the mysterious slow reacting substance of anaphylaxis (SRS-A) – the substance that causes some muscle cells to contract and plays a major role in diseases such as asthma – had enduring implications.

It is remembered as Kellaway’s most profound contribution to experimental physiology.