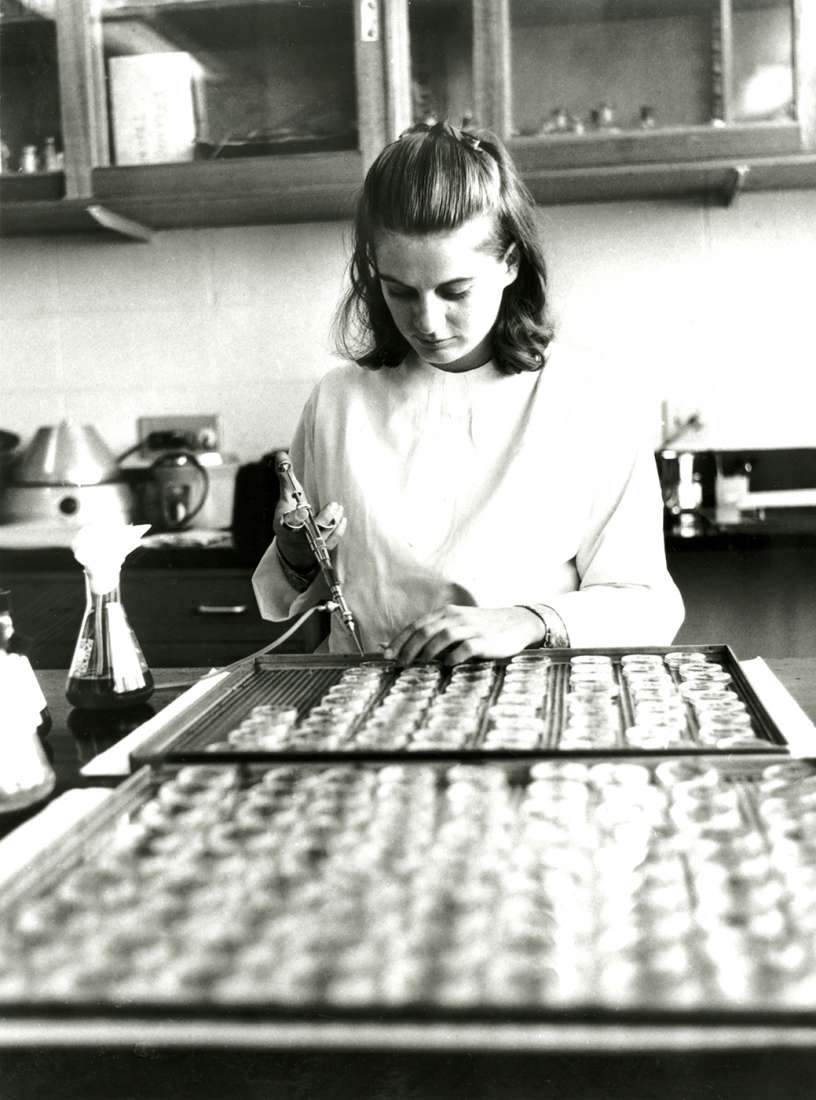

The availability in 1984 of cloned GM-CSF and (later) G-CSF allowed Professor Don Metcalf’s group to test the effects of CSFs in animal models.

“Studies began with bated breath in May 1985, 20 years into the CSF saga” then director Professor Gus Nossal recalls.

Research speaks for itself

One of Metcalf’s well-known sayings at the institute was, “let the research speak for itself”. In this case it does. GM-CSF treatment is found to boost blood cells by 10- to 100-fold, while G-CSF increases white blood cell counts by more than 100-fold over normal levels. “For the first time in 1986 Metcalf was prepared to speculate that recombinant CSFs might be able to help patients,” Nossal says.

The research reveals that CSFs only persist in the blood for a short time, suggesting injections should be given under the skin to let them be absorbed more slowly over time.

Clinical trials of CSFs

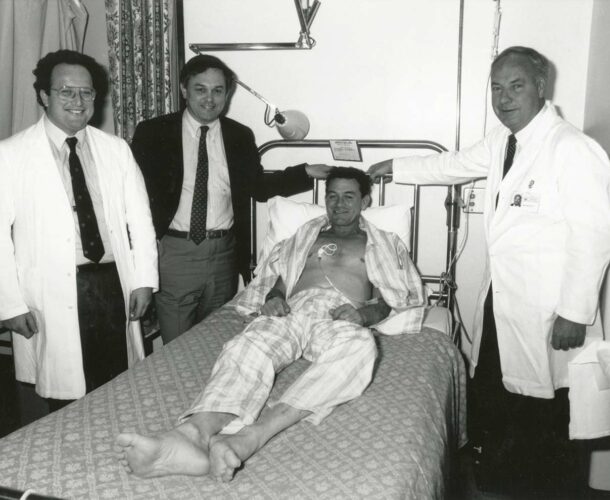

Clinical trials of both G-CSF and GM-CSF were held between the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research and The Royal Melbourne Hospital, spearheaded by Dr George Morstyn and Professor Richard Fox.

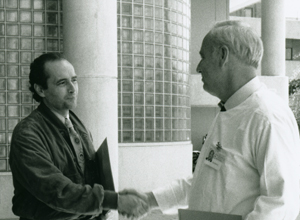

Internationally, Spanish tenor Senor Jose Carreras is one of the early clinical trial patients, receiving GM-CSF to help recover from leukaemia. Carreras was interested to meet the group of scientists who had “helped save his life” and, in 1991 visits the institute to meet Metcalf and his team. On another occasion, a tour of Melbourne coincided with Metcalf’s 80th birthday, and Carreras sings him happy birthday.

“Grouping all the results from cancer patients in Australia, the United States, Europe and Japan together, it was shown CSFs could hasten white cell count normalisation, reduce hospital stay, lower the incidence of fever and infection, reduce antibiotic use, all adding up to a cost-effective therapy.

A surprise discovery

But there is another surprise in store. Working with recombinant G-CSF, Metcalf, Dr Glenn Begley and Dr Greg Johnson note that G-CSF causes a marked increase in blood stem cells in the bone marrow. “Somehow G-CSF, in the in vivo situation, had mobilised progenitor cells in an unexpected way.

In 1988 Dr Uli Dührsen shows that giving patients a four-day treatment with G-CSF has similar results, increasing blood stem cells by a factor of 10.

“For the first time it became possible to think of blood, not bone marrow, as a source of haemopoietic [blood] cells for transplantation,” Nossal later writes.

“The implications for bone marrow transplantation were clear. What has come to be termed peripheral blood stem cell therapy has now become routine. The technique has now largely replaced bone marrow transplants.

Remembering a ‘Eureka’ moment

Metcalf later wrote: “Outstanding in my memory is the day when recombinant GM-CSF was revealed as having produced cellular changes when injected into mice.

The first analysis of these mice was to determine their white blood cell levels. These showed little believable change. During these estimations, the top of a glass Pasteur pipette broke off, fell into my shoe and became embedded in the tip of my big toe. Such was my mounting disappointment that I ignored this minor discomfort.”

However a second procedure confirmed 20 years of research had culminated in a potential treatment.

“As the first fluid was withdrawn, it was of milky opalescence due to the increased numbers of cells, as was the fluid from the second and third mouse. At that point, I realised that 20 years of work on the CSFs had been successful. The CSFs did work in vivo and it was going to be inevitable that, sooner or later, someone was going to find a useful clinical application for the CSFs.

There was a definite feeling of a job completed – at least, complete enough to allow me to stop and remove the glass still embedded in my big toe. A trivial memory? Not really. This is life as it happens at the laboratory bench.”

The force of a vision

At Metcalf’s retirement in 2014, many of his long-time colleagues spoke about the lasting effects of his discovery.

“It was entirely Don’s vision to take this path,” colleague and long-time friend Professor Nick Nicola says. “It was the force of his vision and his personality that attracted a bevy of superstar biochemists, molecular biologists and clinicians to help him ultimately deliver the CSFs as clinical agents that have helped million of people around the world. There are few – if any – current medical treatments that from conception to delivery into practice have been so strongly associated with the force of a single individual.”

Institute director Professor Doug Hilton refers to Metcalf’s strong sense of a medical researcher’s “obligation to cure human diseases”.

“Over the past 20 years, more than 20 million cancer patients have been treated with CSFs and, as a result, have been given the best possible chance of beating their cancer,” institute director Professor Doug Hilton said. “There can be no greater legacy for a medical researcher.”

And blood cancer researcher and haematologist Professor Andrew Roberts speaks of the difference Metcalf’s research have made for patients.

“The highest accolade I could give as a clinical haematologist who treats people with blood cancers every day and performs bone marrow and stem cell transplants every day is Don, we take your work for granted,” Roberts says. “GM-CSF and G-CSF – we can’t imagine a world without them. They have changed the lives of millions of people and every day, in every way, are making a difference.”