It was a brief flirtation with the notion of a political career, back in 1963, that delivered Sir Andrew Grimwade instead into an association with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute that has endured over half its century of endeavor.

An impulsive joiner of things

Back then he was a hot-shot young businessman, an Oxford-educated scientist and the scion of an establishment Melbourne dynasty founded on pharmaceuticals and chemicals. Grimwade was connected, energetic, a self-described “impulsive joiner of things”. When asked to consider taking a seat in parliament he sought counsel from Sir Colin Syme, then chairman of BHP and president of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute board.

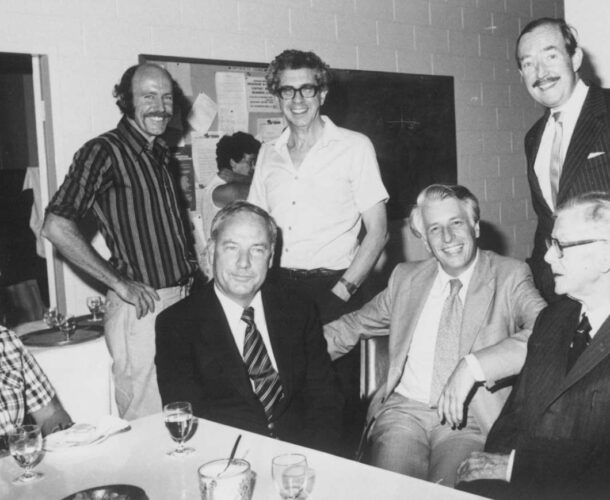

“He said ‘I think you can do more good elsewhere’,” Grimwade recalls. The matter rested there until soon after when he accompanied his mother Gwen, vice president of the Royal Children’s Hospital board, to the opening of the new hospital by Queen Elizabeth on February 25, 1963. “We sat next to her old friends [institute director] Burnet and his wife Linda.

“Burnet leaned over and said ‘I’m glad you are joining the board’. Obviously Colin Syme had decided medical research was more useful than politics.” Grimwade served on the board until 1992, including 14 years as president.

Tight budgets and scarce equipment, but journal papers published

Asked today to nominate milestones of his involvement, he reflects on the physical and financial circumstances of the institute he first knew and how they changed.

In 1963 the Hall Institute – “as all the old timers still call it” – consisted of about 50 personnel. Their ranks were growing but already squeezed within the small Parkville premises the institute had occupied for 20 years.

Science was progressing swiftly, with molecular biology and biochemistry driving discovery. The influenza and immunological work lead by legendary director Burnet, who had been awarded the Nobel Prize in 1960, delivered the institute international gravitas. Budgets were tight and new equipment scarce but the watershed journal papers kept coming.

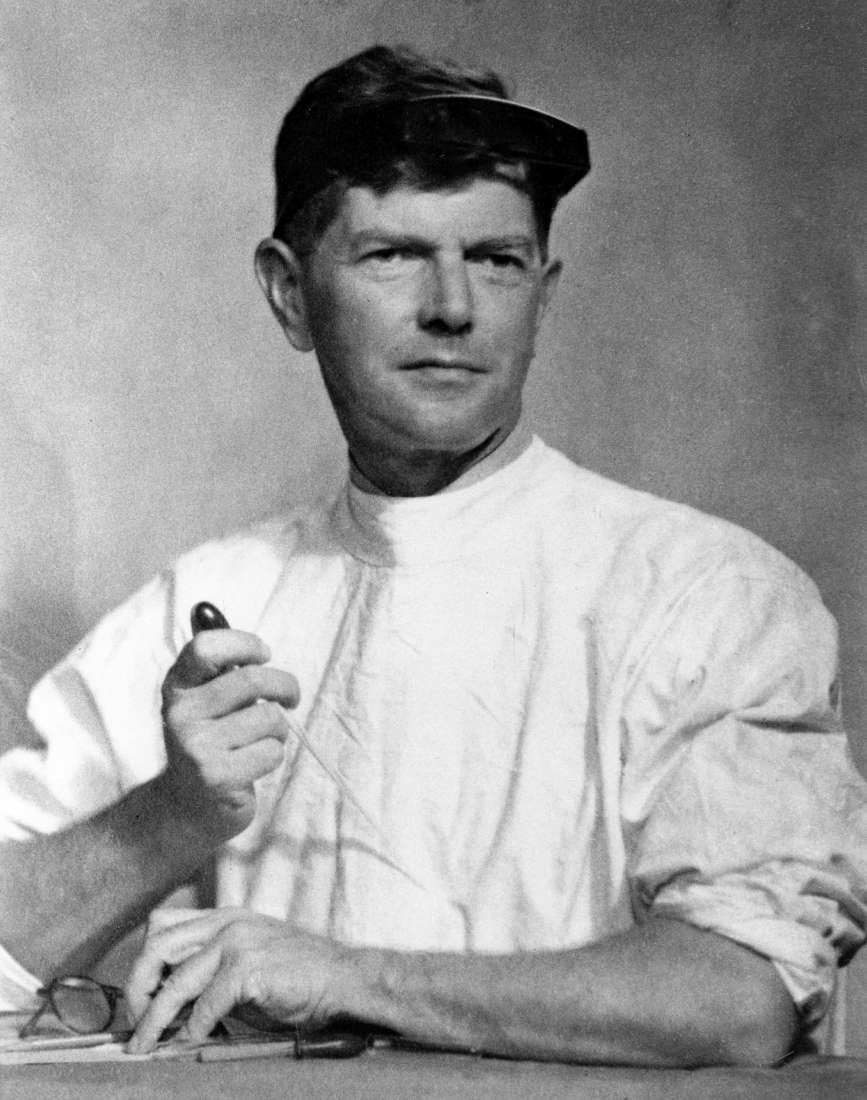

Grimwade got a feel for the place by spending time with each of the lead researchers. They included “a recluse called Don Metcalf ”. To find him required navigating a route through the boil and hiss of the Royal Melbourne Hospital laundry.

Backroom leverage for science

Metcalf had joined the institute in 1954 on a fellowship from the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria. He had already begun investigating his suspicion that some biological mechanism controlled white blood cell production, an inquiry that would occupy much of his professional life and identify “colony stimulating factors” (CSFs), yielding treatments that have now benefited 20 million cancer patients worldwide.

Grimwade had an inkling of Metcalf’s potential, and was determined to improve the scientist’s threadbare circumstances. He suggested to the Vice Chancellor of Monash University that maybe Monash might begin an association with the institute by offering Metcalf a chair, “something Melbourne University had denied as being too difficult”. On learning of Monash’s keen interest, a Melbourne chair for Metcalf suddenly materialised. It would not be the last time that Grimwade would exert such backroom leverage in the cause of better science.

Negotiating funding for a new building

“The second highlight was getting Gus Nossal appointed as director [in 1965],” says Grimwade. He was Burnet’s chosen successor and always the favored candidate, albeit precociously young at 35.

“By then the institute was crammed – all the corridors were full of equipment, refrigerators, files. It was a fire hazard. We’d expanded a couple of floors and recovered the ground floor, but had to negotiate at great length with the hospital for a bit more land.

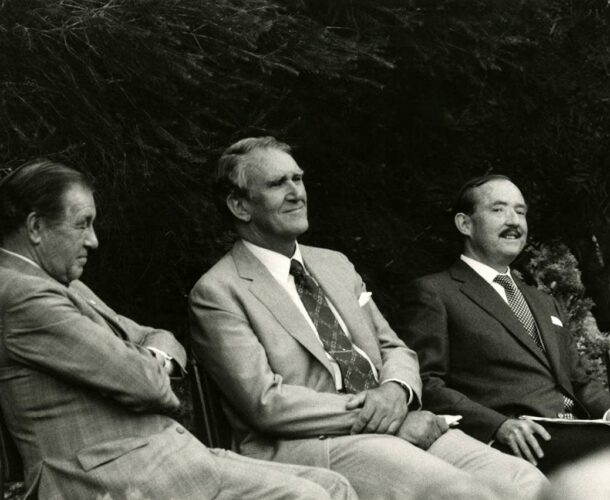

“Gus came along one day and said ‘we need a new building, with capacity for over 250 scientists’. Nossal nominated a budget of $10 million, “and I said in my opinion everything costs twice what you think it will, so we will go for $20 million. We would go to [Premier] Dick Hamer and [Prime Minister] Malcolm Fraser and get them to put in $10m each. Fortunately they were both facing elections.”

Architect Daryl Jackson was given the design brief. “Gus carted the model to the premier’s office. And Dick said ‘$10 million is a lot of money’. And I said we were going to get $10 million from the Prime Minister. And he said ‘I hope you do’.

“Then we went to Canberra – again Gus carrying an elaborate model. I had known Malcolm since we were at kindergarten. He said – gruffly – he would put in $10 million if Dick would. I said ‘leave it to me Gus’. Next day I made a couple of calls and we had our $20 million. No-one knows who was rung first.

“The twist in the tale is that when the building was finished in 1985 it cost $39.9 million – exactly double. But we got the $20 million indexed, which was a little bit of shrewdness neither government saw through. And Gus got his institute.”

Discoveries for world use

Grimwade also nominates a couple of disappointments. Foremost was that as board president, he nominated Metcalf, Jacques Miller and Nossal for the Nobel Prize on two occasions. That none of them were recognised “was a great sadness”.

“The next sadness – and I was the one responsible – was not realising the importance of intellectual property. We never patented anything. If we had patented Don Metcalf’s discovery, this could be the wealthiest institute in the world. But we lived at a time when we were gracious, when a handshake was your bond, and when discovery was there for world use. Now we live in a new world. That has all changed.”

The president’s job

Although Grimwade retired from the board in 1992, he remains closely engaged with the institute. He has observed as the institute once again began to burst at the seams, as science exploded again, and the laboratories went through another expansion and metamorphosis to today contain 1000 people.

The casualty of that growth was the intimacy of the bygone era, but Grimwade believes that many of the old values have endured – “miraculously, I guess. The life of an institute is like the tide of the oceans. It comes and goes a bit.

“I think that where this institute has really been outstanding for 100 years is that it has been a family. People have loved each other, in the old sense of the word. That has come down the line through the directors.

“The president’s job is to keep the governments on side, to help get major donors. And of course help select the chief executive. On that the board has always done a brilliant job.”

In his book reflecting on the institutue under his direction, Diversity and Discovery, Nossal recognises Grimwade for the defining legacy of his adventurous and entrepreneurial contributions to the board.

He nominates in particular Grimwade’s development of improved superannuation, his initiative in forming an ethics committee, and his masterminding of the new building as enduring contributions. “The institute will always remain deeply in his debt.”