The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute is fortunate to be included in the first round of grants made by the Ramaciotti Foundation.

Institute secretary Geoffrey Hays, has made contact with Miss Vera Ramaciotti to express the institute’s urgent need for support. Specifically, there is a need to construct a pathogen-free facility for breeding mice.

The Ramaciotti Foundation has made a generous grant of $150,000 for the building project, and a short-term loan of a further $150,000.

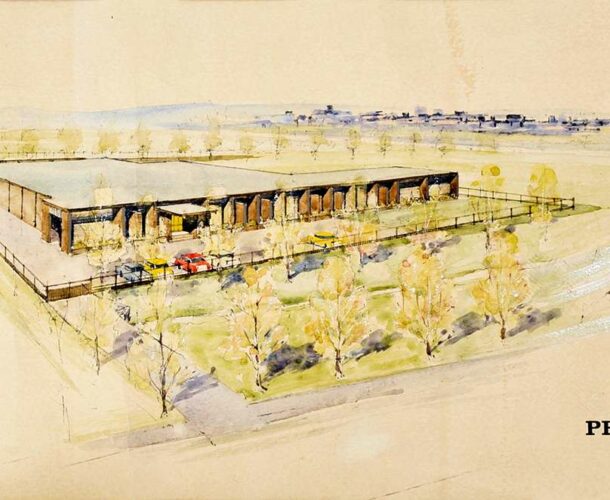

The Clive and Vera Ramaciotti Laboratories are to be opened by The Honourable RJ Hamer, Premier of Victoria. The facility provides both the institute, and the Australian medical research sector at large, with high quality, consistently produced stock.

High working standards ensure an excellent reputation

Clive and Vera Ramaciotti Research Laboratories have been established to enable the breeding of inbred, congenic and mutant mouse strains in clean conditions.

A dedicated staff consisting of animal technicians, animal attendants, administration and engineering staff, work together to ensure the ongoing success of the campus. Their knowledge, commitment to high working standards, as well as the ethical treatment of the animals in their care, ensures the institute’s reputation is second to none throughout the animal research community across Australia.

A day in the life

A day at work for staff at the facility can involve several showers a day. Workers strip off, shower thoroughly, and don clean kit from top to bottom to enter the mouse rooms. If they leave at lunchtime, they shower again. If they move from one mouse room to another, another shower.

Gill Carter, a career in animal care

One pay-day in 1987, Gill Carter sat in her London kitchen, put aside the money for her mortgage and her pile of utilities bills, and contemplated the measly remainder that she would live on for the next month.

“I was working in a London teaching hospital, managing the animal research facility there, and feeling very disillusioned with Thatcher’s Britain.” Then came her kitchen bench epiphany. “I remember thinking there had to be more to life than this. And I had this light-bulb moment. I’m going to Australia.”

In this pre-internet era, she went to the local library scouring for addresses for Australian hospitals and research facilities, and mailed off her CV to as many as she could locate. She had three replies, one of them from Margaret Brumby at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in Melbourne. There was a suitable position coming up in a few months. If Carter could get herself to Melbourne, “we might consider you for it”.

Carter immediately set about selling most of what she owned, and shipping what remained to Melbourne. She managed to secure a residency permit in a mere eight weeks. “And I rang up and said ‘I’m here’.” Her punt paid off. She started work at the institute’s “mouse Hilton” breeding facility a week later.

New job, new country, new romance

On her second day she met Peter, an animal attendant “and we just clicked”. He became her husband. “I blame [Dr] Margaret Holmes” – the institute’s legendary researcher, administrator, and overseer of its world-renowned mouse breeding program. “She found out I was living in a flat without furniture because all my worldly goods were on a ship somewhere.

“She said ‘I’ve got a few bits and pieces, I will lend them to you’. She got Peter to deliver them. So he turned up at my flat with a mattress. And I thought ‘this guy’s keen’. And he never left.”

On working with animals

Carter worked for the next 27 years at what is regarded as one of the world’s finest research breeding facilities, and managed the germ-free mouse program – the only one in Australia. These are mice with no gut bacteria at all, and their care and maintenance is a highly specialised field. They have been critical in programs such as Professor Len Harrison’s work on diabetes.

Carter got into animal technology because she was – and is – an animal lover. The fact that these animals are enlisted, and die, in the pursuit of research into human health may confront some people who regard themselves as animal lovers, but Carter is clear-eyed and thoughtful about her motivations and the importance of her work.

Difficult but important work

“I’ve done this job for 40 years, and I have seen an enormous number of advances made in medicine for humans and for animals that would not have occurred if those animals had not given their lives,” Carter says. It’s not easy work, but valuable. She always encouraged researchers to talk to her staff about their mouse models and how they used them.

She saw her first priority, in managing animal facilities for medical research, “was always as the advocate for the animal, and the animal always comes first.

“One of the things I always admired about the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute is that it took the animal efforts very seriously. The welfare of the animal is always very important, and it has to be.

“When I first started in this job we thought that if we gave the animal food and water and a clean bed we had done all we had to do. But now we understand that environmental enrichment is also important. The type of life an animal leads while it is with you is important, and if an animal is stressed in any way the experimental result is affected.” And so the mice have toys and distractions. Like what? “One day I came to work and someone had hung surgical masks in the cages, and the mice were swinging in little hammocks.”

One of the breeding lines used in the institute’s mouse models has been evolved for laboratory work since 1900 – descendants of the famous laboratory line bred by C.C Little for the Jackson Laboratory in Maine, USA.

Retirement

Carter retired in 2014, and now works with Peter as a full-time farmer. She takes great pride in her contribution to science over her years at the institute and in London. “The thing with research is that there are lots of little steps. And certainly we’ve helped with lots of those steps. I wouldn’t say that we cured cancer, but we’ve helped the researchers understand and progress.”