Dr Kellaway established three departments: physiology, headed by himself; biochemistry, headed by Dr Henry Holden; and bacteriology, headed by the young Dr (later Sir) Frank Macfarlane Burnet.

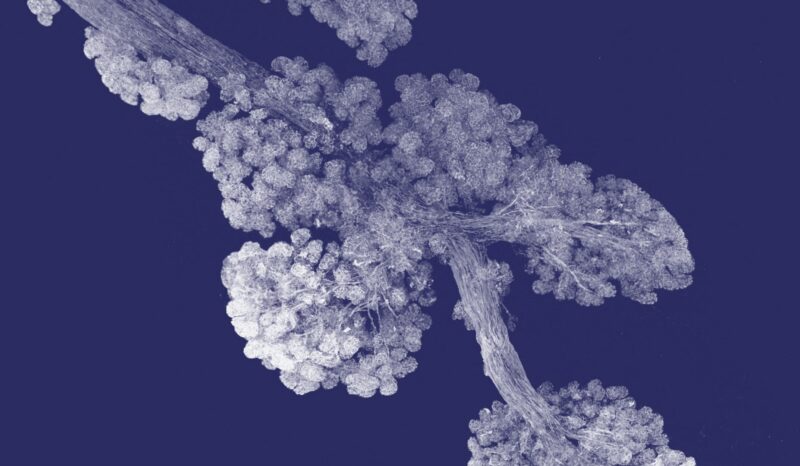

In 1925, Dr Kellaway sent Dr Burnet to the Lister Institute, UK, where he worked on bacteriophages and secured his PhD. Upon his return, Dr Burnet continued to make seminal discoveries in bacterial and phage genetics but moved more and more into virology.

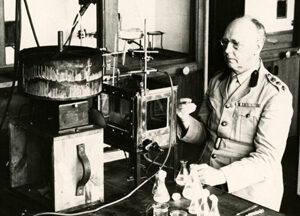

Together with Dr (later Sir) Neil Hamilton Fairley and Dr (later Sir) Harold Dew, Dr Kellaway focussed on hydatid disease and venoms of Australian snakes, spiders and mussels. Sir Hamilton Fairley went on to a major career in tropical medicine, first in India and then in London and was responsible for a program of prophylactic antimalarial treatment that was critical for the Australian armed forces during the World War II.

Four of Dr Kellaway’s small staff – Dr Wilhelm Feldberg, Dr Neil Hamilton Fairley, Dr Burnet and Dr Kellaway himself, in 1941, were eventually to be elected Fellows of the Royal Society.