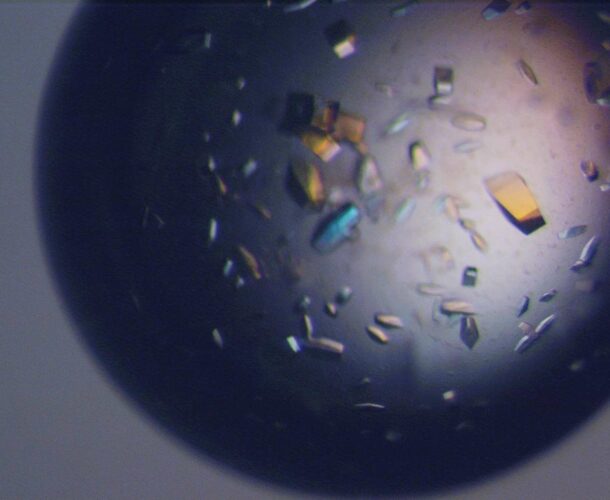

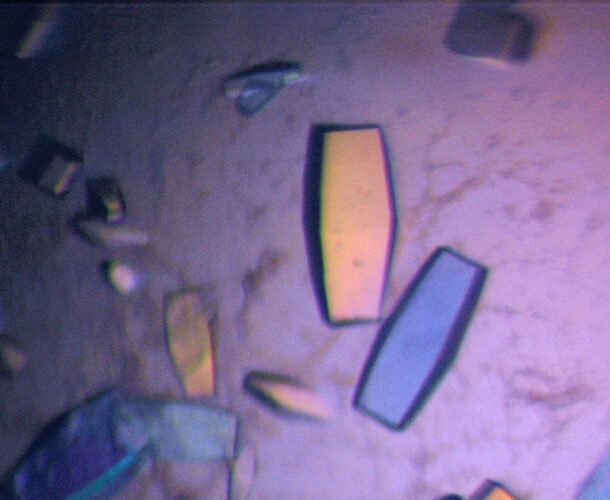

In 1985 Dr Emanuela Handman’s work as part of a world-first program to explore the immunology of parasitism, led to the discovery that the carbohydrate coat of Leishmania is used by this parasite to infect host cells, making it a potential target for vaccine development.

A chance discovery

“By a chance discovery, I ended up making an impact in an area absolutely out of my sphere, which was glycobiology (involving sugars and sugar-containing lipids).” Handman’s knowledge and curiosity about one of the molecules on the surface of the Leishmania parasite led to the discovery that it was not a protein, as suspected, but a kind of protective sugar coating, opening up a whole new field of investigation of the parasite’s structure and biochemistry.

Institute scientists inspire in Jerusalem

In the mid-1970s, when Handman was deep in her reading for her PhD at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, research from a little research institute on the other side of the world kept turning up in the prestige journals, compelling her attention.

“There were exciting papers in immunology and genetics coming out all the time” from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, she recalls. The young parasitologist’s interest in the faraway institute was further nourished when its then director, Sir Gustav Nossal, delivered a series of “enthusiastic and inspiring” lectures in Jerusalem.

Celebrated scientist from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Dr Graham Mitchell, also visited, getting a rock star reception in the immunology department, where “all the students were piled up watching him” as he demonstrated his technique.

The Amazon or the Yarra

Young Handman was keen to pursue a less-travelled path after completing her PhD, tossing up between Belem, at the mouth of the Amazon, and Melbourne. What the Yarra lacked in romance it made up for in the prospect of working in Mitchell’s program exploring the immunology of parasitism. His core interest was in how the human immune system determined if and when a parasite might trigger disease, and how it influenced its severity.

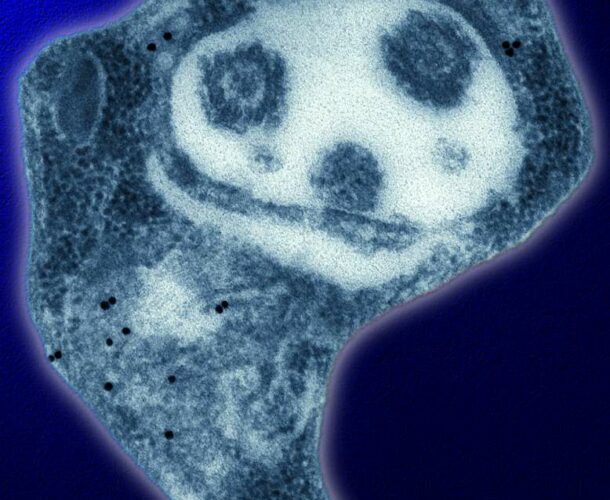

Handman was encouraged to join Mitchell’s team because of her expertise in investigating leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease spread by sandfly bites.

Though rarely seen or heard of in Australia, except among some recent migrants or travellers, leishmaniasis afflicts some 12 million people across large swathes of the tropics, subtropics, Middle East and southern Europe. It most commonly causes skin sores but in one form, visceral leishmaniasis, it can affect internal organs and cause death. Today the World Health Organization estimates it kills 20,000 people a year. It also has a devastating indirect toll by sabotaging development programs and socio-economic opportunities.

A meaningful career

Handman suspected, having been among the first to set up a mouse model to examine the disease, that the genetics of the host were critical to if and how the disease progressed. The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute offered the chance to explore this because “it had an amazing mouse facility, there was not another in the world as good.

“That was an attraction for me, to be able to look at all these different strains of mice and figure out if the genetics of the host did in fact determine the severity of the disease.” Over the years the work yielded important early insights into T cells (immune response cells). “It was very creative, very forward-looking for Gus to support something like this and for Graham to embark on it. I am very grateful that they did.”

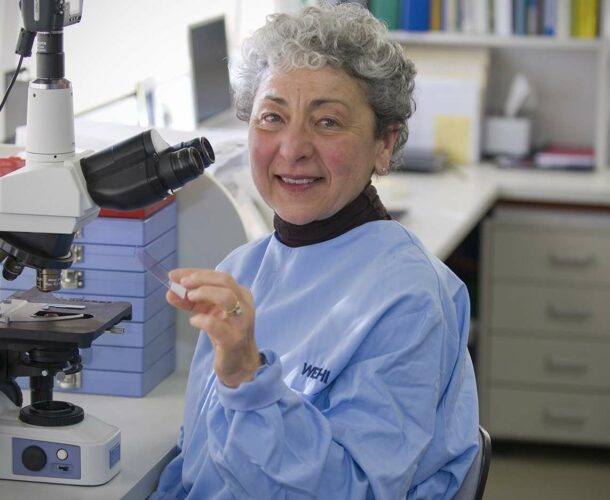

It was the beginning of a meandering career. “I was never one particular kind of ‘ologist’,” she reflects, now seven years retired.

A deep connection remains

Towards the end of her career Handman returned to the role of host genetics as the emergence of new tools – transgenic and ‘customised’ laboratory mice – allowed scope to go deeper into the questions that preoccupied her early career.