In 1953 Professor Gordon Ada discovers that the influenza is made up of RNA, not DNA. RNA viruses are highly unstable, and the discovery helps to explain how flu mutates and recombines. This explains how it evades discovery by the immune system and, following on from earlier work about the virus’ ability to exchange genetic material, provides crucial insights for future flu vaccine development.

Ada: a background

One year, while he was still in high school, Gordon Ada received The Science of Life as a Christmas present.

He soon became immersed in its pages. The book was the first step in a lifelong exploration of science that saw Professor Ada, the fourth child of the chief electrical engineer of NSW Railways, become one of Australia’s most influential microbiologists.

In 1944, with a Bachelor of Science under his belt and a Masters and Doctorate still to come, Ada began work as a researcher at Melbourne’s Commonwealth Serum Laboratories. From there, he moved to London’s National Institute for Medical Research where he mastered new biophysical techniques to study protein.

Ada returned to Australia in 1948 to join the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute at the invitation of Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, who asked him to establish the Biochemistry and Biophysics Research Unit with Henry Holden. At this time institute’s research focus was centred on viruses, in particular influenza, which Burnet managed to isolate in chick embryos.

A critical flu discovery

When it came to influenza research almost every senior scientist was free to find their niche— and for Ada and his colleague Alfred Gottschalk that meant investigating the biochemical dimension of the virus-host cell interaction. Ada’s major breakthrough came in 1953 when he found that the flu virus’ genes were not composed of DNA but of the related molecule, RNA. The discovery was of critical importance.

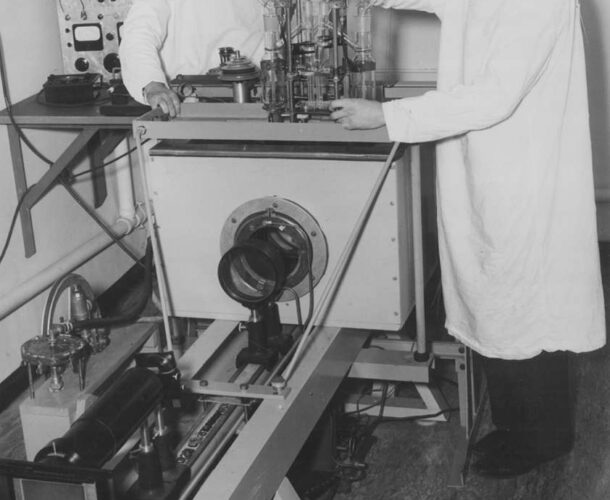

To investigate the genetic basis for influenza, Ada and Miss Beverley Perry decide to first purify the nucleic acids from the virus particle before analysing its contents. Ada’s study reveals nucleic acids only make up one per cent of the virus particle by weight, and that it exists as single-stranded RNA rather than the double-stranded DNA found all living organisms.

Ada’s discovery enables further research into interrupting influenza’s lifecycle by targeting the replication mechanisms used by RNA. Interrupting RNA replication results in an incomplete virus, providing a potential strategy for reducing the efficacy of the disease. The research team also discovers that concentration of RNA within the virus particle correlates with how infectious the influenza strain is, further unraveling secrets of the virus.

Shift to immunology

Along with his Walter and Eliza Hall Institute peers, Ada’s focus later shifted from virology to immunology. He applied modern methods to trace where vaccine molecules — antigens — go after injection. Though Burnet himself found it near impossible to produce a “readable” account of Ada’s work because of its highly complex, technical nature, an obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald, written after his death in 2012, credited him with deepening scientists’ understanding of “immunological memory, the fact that booster shots of vaccine work better than the first dose.” Ada also built on the knowledge of how white blood cells fabricate protective antibody molecules in a study intriguingly called, the “hot antigen suicide” experiment.

A new home

After two decades at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, by which time Ada’s work had been cited in noteworthy journals more than 10 times, he took up a position at the Australian National University. The new role was as head of the Department of Microbiology at the John Curtin School of Medicine— for which, as Burnet wryly observed, the institute “served almost as a nursery” for distinguished talent. Under his leadership the department won international prestige as a centre for the study of the cellular immune response, with researchers Peter Doherty and Rolf Zinkernagel laying the foundations for work that culminated in a Nobel Prize.

Ada retired from the John Curtin School in 1987. A year later, during a lecture at the International Congress on AIDS in Stockholm, he asserted that “there will not be a vaccine against HIV for some time.” The statement was so contentious it prompted an invitation for him to join the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health in Baltimore, where he became director of the Centre for AIDS Research.

In the early 1990s he returned to Australia, remaining active in the field of immunology. His advocacy for vaccination continued after his retirement when he co-wrote a book and spoke regularly to community and school groups. On fair weather days he could be found sailing on Lake Burley Griffin.