More than 70 years after he began studying medicine at the University of Melbourne, Professor Ian Mackay still hankers to do what he has done all his life, resolve medical riddles.

The man who was still running in the winter and surfing in the summer at age 90 chafes a little at the physical restrictions of a broken hip. Meanwhile his scientific mind scratches away dispassionately at the questions posed by an aging body.

“If I were to have a second career, I would make it the application of molecular biology to the changes associated with aging,” Mackay says. “There is no doubt that it is a partly immunological, partly molecular process – damaging DNA mutations going on all the time.”

What are the physical and mental processes that erode even the most finely tuned bodies and minds, he asks. “Why are they so regular? Why do grand slam tennis winners stop getting grand slams? What’s happened to Roger Federer?” In the old days at the Hall Institute he would have taken these questions to morning tea and shared with whoever he happened to sit next to, as was the ritual.

“But it is not to be,” he says. “As Gus (Nossal) put it, we can’t rerun the tape”.

That said, sitting surrounded by a small collection of his books and papers – fragments of an archive that includes over 700 journal articles on autoimmunity and mighty tomes that remain the definitive word on the subject – he plainly couldn’t have crowded much more onto the tape for the first run.

As a tribute in the Journal of Autoimmunity on the occasion of Mackay’s 80th birthday observed (and this author can only agree), “explaining his contributions to human immunology … is much like trying to summarize War and Peace for a high school primer”.

Early setbacks

Mackay’s early career encountered setbacks that could have put it entirely off course. As a young doctor he contracted tuberculosis and spent nine months in a sanatorium, much of it fretting about losing his place in mainstream medicine. He took a job in post-war Germany as a medical officer at a displaced persons camp, examining more than 7000 refugees for possible migration to Australia.

In 1950 he went to London. His personal experiences had inspired him to become a chest specialist, but “unfortunately they weren’t looking for a man answering my description”. After the third strike he encountered a woman he “didn’t know from a bar of soap” at Hammersmith Hospital. She was Sheila Sherlock (later Dame Sheila), a pioneer of the emerging field of hepatology.

“She said ‘you look a bit down in the dumps – what’s happened?’” Mackay told her his story. “She said ‘come and work with me’. I said I didn’t know a thing about livers. She said ‘no problem, we’ll teach you’.”

Arriving at the institute

Thanks to her training and recommendations he made his way to the United States and positions at the University of Washington in Seattle and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre in New York. In late 1955 a letter arrived from Dr Ian Jeffreys Wood, a mentor from his student days, now running the institute’s Clinical Research Unit, a joint initiative with The Royal Melbourne Hospital.

Would Mackay be interested in joining him? “It was a very nice letter that he wrote, and I just felt I couldn’t refuse. He was a wonderful man, and I’m sure a lot of my success can be tracked back to Ian Wood.”

Mackay arrived at the institute just in time for director Macfarlane Burnet’s “famous edict” shifting its direction. “I recall the day he assembled the staff, such as it was then – it was a relatively small place – and just said ‘we are switching from virology to immunology. And said it in such a way that the virologists, who outnumbered everyone, felt they either became immunologists – or they left.”

Mackay did as instructed. “And although I knew as much about immunology as I knew about livers when I met Sheila Sherlock, the more I learned, the more fascinated I became.” He was particularly intrigued by the notion of autoimmunity – that an individual’s own immune system might turn on itself, causing defined, treatable chronic disease. The theory was doubted, even derided.

Death sentence to manageable disease

As a liver specialist, Mackay was interested in the hepatitis virus. “In those days it didn’t seem it was a chronic disease, and yet we gathered in the Clinical Research Unit a group of young women who had a severe, progressive, frequently mortal type of illness.” Mackay wondered if their hepatitis might be an autoimmune condition, “nothing to do with the virus”, and seized the initiative to find out.

An American researcher, Dr Carleton Gajdusek – who would later win a Nobel Prize for his work on kuru – was visiting the institute and trying to develop a specific test for viral hepatitis.

Unbeknown to Gajdusek, Mackay slipped a batch of sera from his patients into the next round of tests. The test didn’t work on viral hepatitis cases, but produced some striking positives using Mackay’s samples. This yielded a revelatory diagnostic test – the autoimmune complement-fixation test that clearly indicating certain patients were mounting an antibody attack on their own tissues.

Mackay’s role in this was little known. In his history of the first 50 years of the institute, Burnet referred to Gajdusek’s discovery of the diagnostic test as having been facilitated by “a form of serendipity which need not be elaborated”.

“They didn’t include me on that paper, which is something I feel mildly pained about because that was the discovery element,” Mackay recalls today. But it did bring insight, opening the door to effective treatments that quickly turned what formerly had been a death sentence for young women into a manageable condition.

Autoimmunity: a new era

And it ushered in a new era of medical investigation at the institute, with Mackay and Burnet collaborating in the clinic and the laboratory, investigating implicated autoimmunity in many familiar but hitherto unexplained diseases: gastritis, lupus, Sjögrens disease (dry eye), multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and others. By the early ‘60s, they had enough to “lay it on the line”.

As Gus Nossal later reflected, until then “most of the diseases within the autoimmune umbrella were listed as ‘of unknown cause’. Within a decade or so their autoimmune nature was revealed … In many ways Mackay and Burnet’s book The Autoimmune Diseases, published in 1963, was the key signpost”.

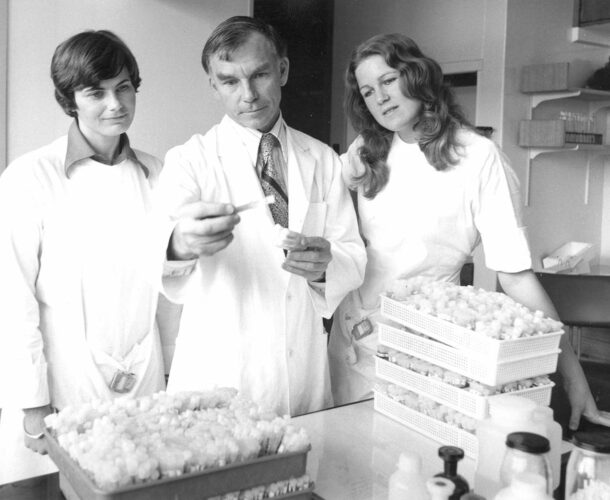

As well as his own achievements in researching and treating autoimmune disease, Mackay continues to find “ongoing pleasure in the successes of the trainees who have gone through the unit in my long tenure”. And he reflects with satisfaction on the professional and personal relationships developed over his 24 years at the institute.

Burnet’s writings had given him “guru status – though that was not a word used in those days. And each of us, the four unit heads – Gus Nossal Don Metcalf Jacques Miller and myself – had an international reputation. That gave us a sense of wellbeing – like the Hawthorn football team, if you keep on winning, you feel good.

There was that collegiate aspect of our lives. And then within each unit, certainly within my unit, we had a very social life together. I think it was a happy group.”