The understanding of how platelets are formed is revolutionised. Previously the accepted theory has been that platelet are produced by programmed cell death (apoptosis). Drs Emma Josefsson and Chloe James, and Professor Benjamin Kile have found that megakaryocytes – large cells in the bone marrow that are platelet factories – must actively avoid cell death in order to produce platelets.

Low platelet numbers are a potentially life-threatening side-effect of some cancer treatments. This insight opens potential for new ways to maintain platelet numbers in patients undergoing chemotherapy.

A research obsession

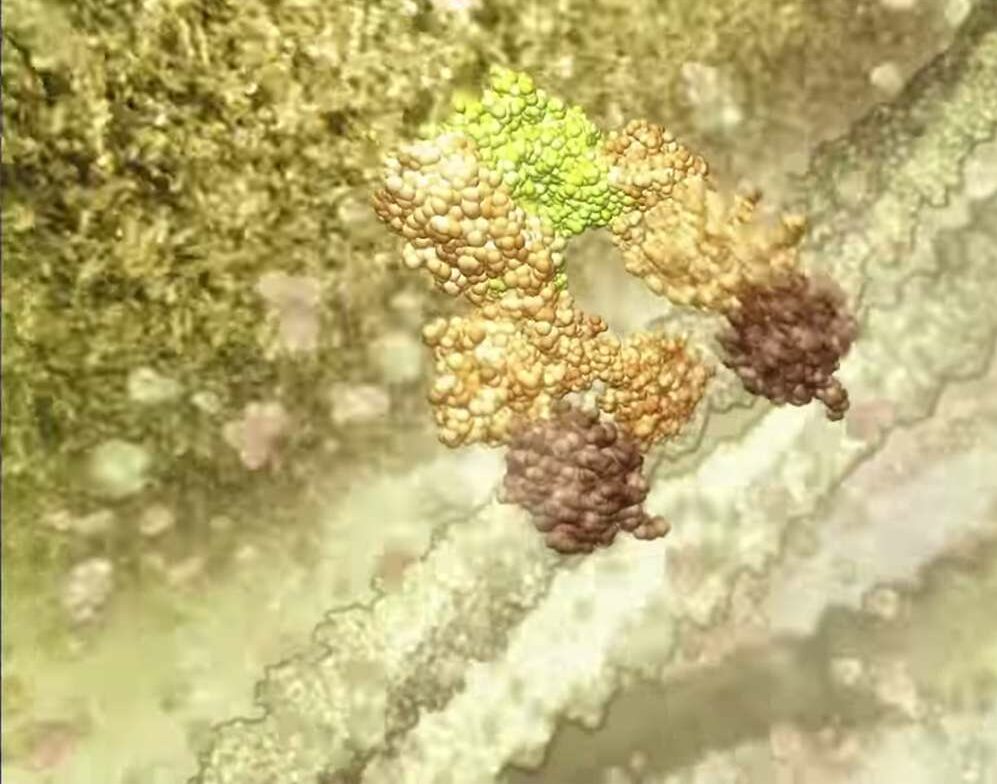

Platelets – the disc-shaped cells that circulate in our blood and clump together to stop us bleeding from wounds – are Dr Emma Josefsson’s research obsession.

Her specialty has yielded surprising insights that have paved the way to some powerful new cancer therapies.

My laboratory is working more and more on the cancer angle in platelets, because they have been shown to promote the spread of tumours – or metastasis,” Josefsson explains. “They secrete a lot of different molecules, and we are looking into the mechanisms of those in different types of cancers.

“Platelets are both good guys and bad guys. We need them not to bleed, they are very important to us, and we can’t have too few of them – it is very dangerous. But unfortunately it also appears they become activated in a cancer setting, where they recruit other immune cells and start releasing molecules in the wrong places. So when you have a tumour and it progresses, spreading into other places, the platelets might have a role in that.”

From art to horticulture to biomedical science

A life in science was not what teenage Emma Josefsson had in mind for her future as she made her choices for university back in her native Sweden.

Science was her fallback after she missed out on selection to art school. But Josefsson quickly discovered a passion and an aptitude for biology, “for figuring out how things work”. Art’s loss became medicine’s gain.

Initially she was captivated by plants, but “I then thought I would do something with more a medical track, because it felt like a meaningful thing to do”. She studied pharmacology and science and earned a place at Harvard Medical School, where she pursued her masters’ thesis in a laboratory studying platelets.

Pursuing scientific questions across three continents

The Harvard experience was defining, she says, because “I had inspiring people working around me, and I was fortunate with my project, which produced some exciting data”. She returned to Sweden’s University of Gothenburg to complete her PhD, setting up a collaboration with Harvard and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Here, Josefsson continued her research into platelet storage and into whether changes to their glycobiology (sugars) might help them circulate better.

She kept pursuing these questions as a postdoctoral fellow in Boston, accumulating six years in the Harvard laboratory. Then as she pondered her next step she came across a poster displaying breakthrough work by the institute’s Professor Benjamin Kile at a research conference in 2007.

“He was about to publish a paper in Cell. The poster was about that work – the regulation of survival of platelets by cell death processes.” Intrigued to learn more, her inquiries resulted in an invitation from Kile to join his team in Melbourne. Having long nurtured a dream of living in Australia, Josefsson leapt at the idea.

Inspiring collaborations

Seven years later, and leading her own laboratory, Josefsson is working with clinician-scientist Dr Kylie Mason to discover what role platelets play in leukaemia and lymphoma development. Josefsson is also collaborating with other institute specialists to look at their role in ovarian and lung cancers.

These collaborations are what have kept Josefsson in Melbourne. With the expertise, equipment and range of techniques available at the institute, “if you have your ideas and your funding, you can quickly get where you want to go scientifically because it is so well set up”.

Lately her collaborations have reached outside the laboratory, involving more consumers – cancer survivors and families impacted by cancers who are increasingly being encouraged to help shape the scientific work.

Award-winning research, a ‘privilege’

Last year, Josefsson was named joint-winner of the institute’s most coveted honor, the Burnet Prize.

The prize recognized Josefsson’s work – born out of her collaboration with Kile – on the factors controlling platelet production.

I’m really passionate about doing this science. I see it as a privilege,” Josefsson says. “We could find something that has a big impact, and that is something that drives me. I love that challenge, and interacting with interesting people.