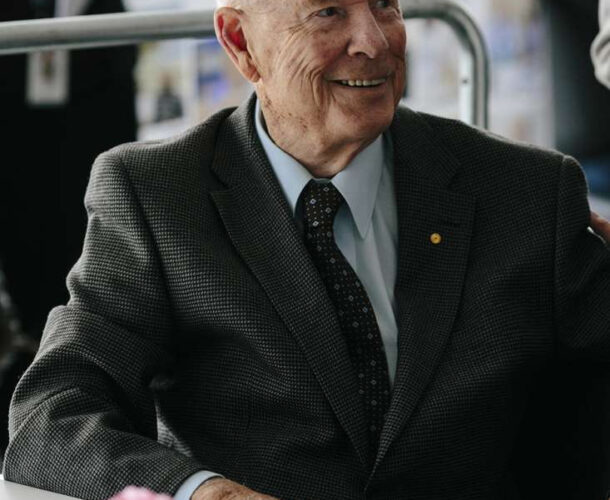

Professor Don Metcalf dies, aged 85, from pancreatic cancer.

Although having officially retired in 1996, Metcalf continued his work with characteristic determination and passion for a further 18 years. In his last months, with poor health finally preventing him from coming into the institute, he requests a microscope be set up at home so he can continue working as long as possible.

For 60 years Metcalf had remained actively engaged in research at the institute. His, and his colleagues’, pioneering discovery of colony stimulating factors is the result of decades of painstaking experimentation, benefitting 20 million cancer patients by the time of his death.

To honour an inspirational scientist, known the world over as ‘the father of modern haematology’, the Metcalf Scholarship Fund is established to support the next generation of young scientists.

A tribute to Professor Don Metcalf

Donald Metcalf – Don to most everyone with whom he worked – was a Colossus of science.

Working at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and supported by Cancer Council Victoria from 1954 to 2014, Don stood astride the world of haematology (the study of blood cells) for 60 years.

The achievements of Don, the scientist, are legion. Don introduced cancer research to the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute at a time when its director, the Nobel Prize winner Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, viewed cancer as an “inevitable disease”, with “anyone who wants to do cancer research, either a fool or a rogue”. Don politely ignored him.

Discovering CSFs

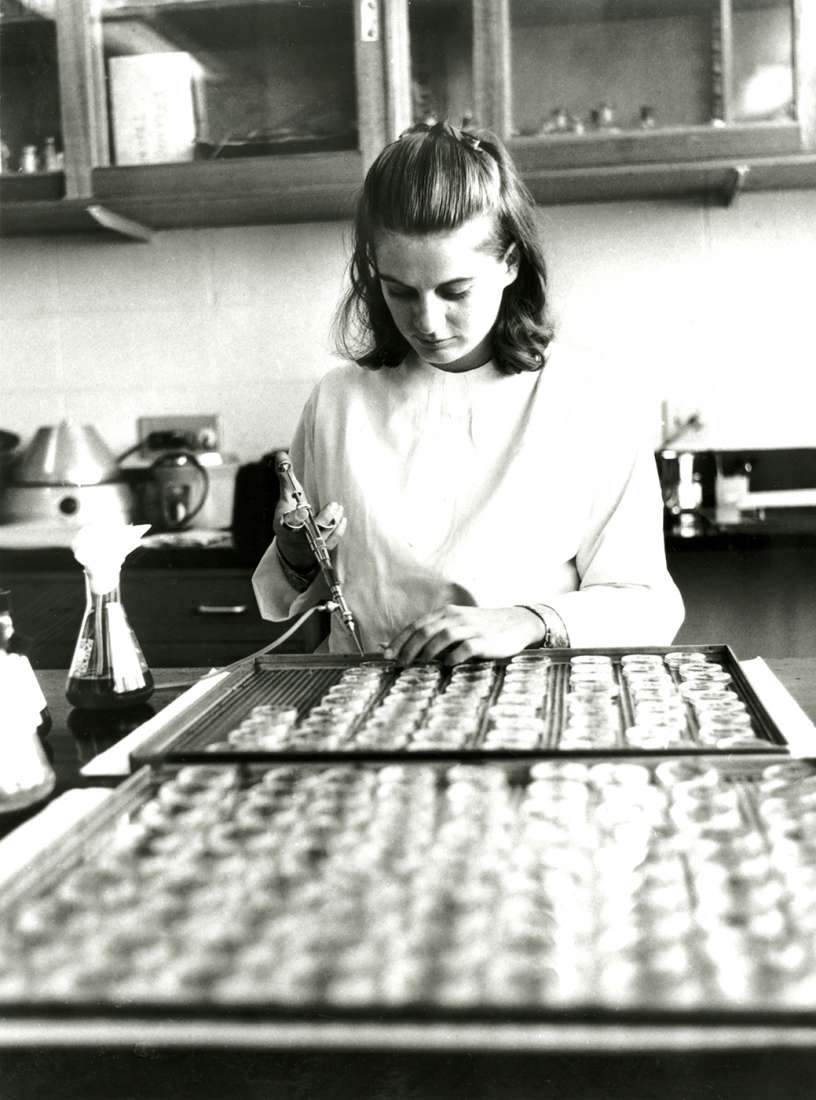

Studying leukaemia in 1964, Don and Ray Bradley, from The University of Melbourne, discovered it was possible to grow bone marrow cells in plates of partly set agar jelly. Don’s genius lay not in this breakthrough, but in the realisation that it could be used to understand the cellular basis of blood cell production and to discover the hormones, which he named colony-stimulating factors (CSFs), that regulate blood cell production in the body.

Don worked single-mindedly on this theme for the next 50 years. He characterised blood stem cells and their daughter cells, which are committed to producing the multiple types of white blood cells that fight infection and prevent bleeding. In doing so he made the blood cell system the ‘poster child’ of medical research and shone a light into the darkness for those who followed him.

Championing collaboration

Don also understood his limitations. He knew he needed collaborators who would take him out of his comfort zone, so he assembled a team of researchers who worked with him for 40 years. Decades ahead of its time, his model of collaborative, multidisciplinary science shaped the culture of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and is now seen by scientists as almost mandatory if big problems are to be tackled successfully.

After two decades, Don and his team succeeded in isolating four of the blood CSFs, paving the way for their mass-production and clinical testing. Don found that injecting the hormones into animals resulted in a rapid increase in the number of blood cells responsible for battling infection and surmised that they might be used to help cancer patients overcome one of the major side effects of chemotherapy: a loss of white cells and susceptibility to life-threatening infection.

Don’s hunch about clinical use was proven correct. Over the past 20 years, more than 20 million cancer patients (including Spanish tenor Jose Carreras) have been treated with CSFs and, as a result, have been given the best possible chance of beating their cancer.

CSFs are now standard treatment and every year the number of people alive because of Don’s work grows.

An institute icon

Don was also loyal. He was loyal to the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, working there almost continuously for 60 years despite lucrative offers from all over the world. Don enjoyed the ‘tyranny of distance’, which he believed made it easier for Australian scientists to pursue highly original research, away from the latest trends and fads.

Don was human – he was no uncaring science machine. He loved banter over afternoon tea, often laughing until tears streamed down his face at some silly anecdote or remark. He loved an annual week on the Sunshine Coast with his wife, which included body surfing, into his late 70s, on waves of any size. He enjoyed a meal and a glass of wine with friends. And more than anything he loved his family – his wife of more than 60 years, Josephine (Jo), his four daughters and his six grandchildren meant everything to him. He knew, and often publicly acknowledged, that without them he would have achieved little of note.

Don enjoyed relative good health until August 2013. Feeling under the weather, he went on leave hoping some time away from the laboratory would rejuvenate him. He returned feeling worse and was quickly diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer.

Knowing the likelihood of cure was not high, his priorities were to undertake some treatment to give him a few extra weeks or months so as to avoid letting down his collaborators and, most importantly, to spend as much time as possible with his beloved Jo and his daughters – but how to do both of these things? The solution for the scientist and family man until the end – have his microscope moved into his home.

Don performed his last experiment in October and died surrounded by his family on 15 December 2014. He would have wanted it no other way.

– Professor Douglas Hilton, Professor Warren Alexander and Professor Nicos Nicola