Sir Gustav Nossal has a vision to bring molecular biology to the institute. Luckily for him, a young Suzanne Cory is homesick and Jerry Adams is in love.

The Adams-Cory laboratory goes on to produce major impacts into the understanding of immunology and the development of cancer.

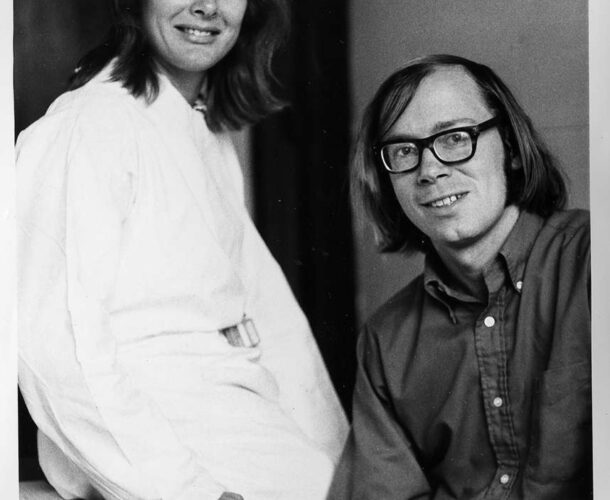

Poised to launch their careers

On honeymoon in 1969, Suzanne Cory was introducing her American husband Jerry Adams to her hometown and her alma mater, the University of Melbourne, when she spotted a display of a just-published book. Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet’s autobiography Changing Patterns would alter the course of their lives, and of medical research in Australia.

The couple had met at the MRC Laboratory for Molecular Biology in Cambridge, England, the crucible of genetic research. Poised to launch careers in the exploding discipline they were being courted by pace-setting institutions. It seemed inevitable that they would take up invitations to work in Europe or the US. Trouble was, young Cory was homesick.

“I missed my family, and I missed the landscape and the sense of humor,” she yearned to come back to Australia to work, “but it didn’t seem fair on Jerry”. Molecular biology had barely crept into the undergraduate syllabus in Australian universities. She didn’t imagine that there would be any place here for their expertise until Burnet’s book prodded recollection of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, which he had lead for 21 years until 1965.

Looking for a place to tackle big questions

“I didn’t know much about the institute, though I had been educated across the road. But Sir Gustav Nossal had given a guest lecture towards the end of my degree, and you never forget him,” she says.

As soon as we walked in the door and started talking to people we knew they were the kind of scientists we were used to. They were in a totally different field – it was all cellular immunology then. But they were as excited about science as we were.

The couple was “looking for a place that was world class, where we could tackle big questions.” Might they have found it in Melbourne?

They pursued this notion in Switzerland, where as postdoctoral researchers they began their enduring and internationally lauded scientific partnership. They arranged to meet Nossal, who was visiting on sabbatical. “We were rather chagrined when he said we could apply (to the institute) as postdocs – we thought we were past that stage.”

Undeterred they sought him out again. “We were in the corridor at the World Health Organisation in Geneva. And Don was there, and he sort of held people at bay while we had this conversation with Gus.

“The reason we were so willing to shift into immunology was that we were quite fascinated by the boldness of the concepts it had developed. There were some really big, important questions being asked.

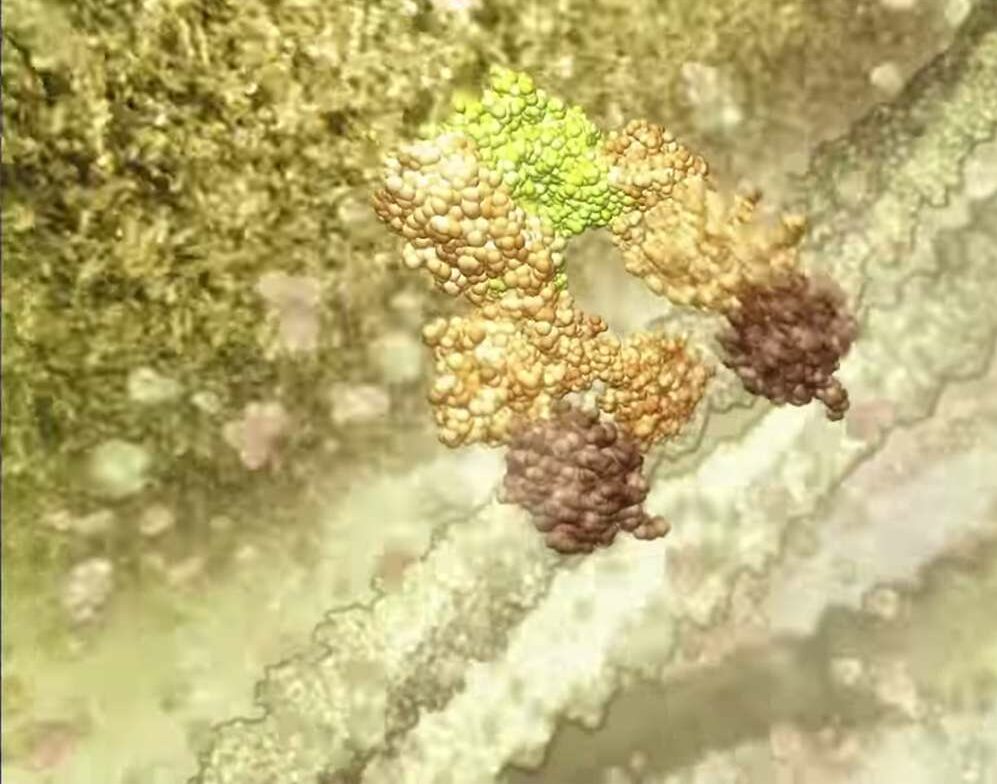

“We were quite convinced molecular biology was going to open up immunology, and that the time was right to move into this more complex system. And we managed to convinced Gus.”

Invited to start a laboratory in molecular biology at the institute, they excitedly drafted their requirements and dispatched the equipment wish list to Melbourne. But when they arrived in 1971 they were shown into an empty storeroom with a couple of benches, a fume hood and some apparatus they assumed were museum pieces (they weren’t). They set to work.

The genetic revolution and a huge gamble

It was three years before they had their first big breakthrough – a major insight into the structure of messenger RNA that gained international interest and more grants. “Our science started going well thanks to this wonderful institute, and we ended up spending our entire careers here,” says Cory.

She still sounds surprised. With hindsight it seems natural that molecular biology entered the institute then, opening the way to gene cloning in the nick of time for the institute to become a force in the genetic revolution. “But it was a huge gamble, on all sides.

Somebody without Gus’ vision would not have taken the gamble. And if I hadn’t been so homesick I would not have taken the gamble. And if Jerry had not been so in love he wouldn’t have taken the gamble.

And yet the planets aligned. The Adams-Cory laboratory had a major impact on the understanding of immunology and the development of cancer.