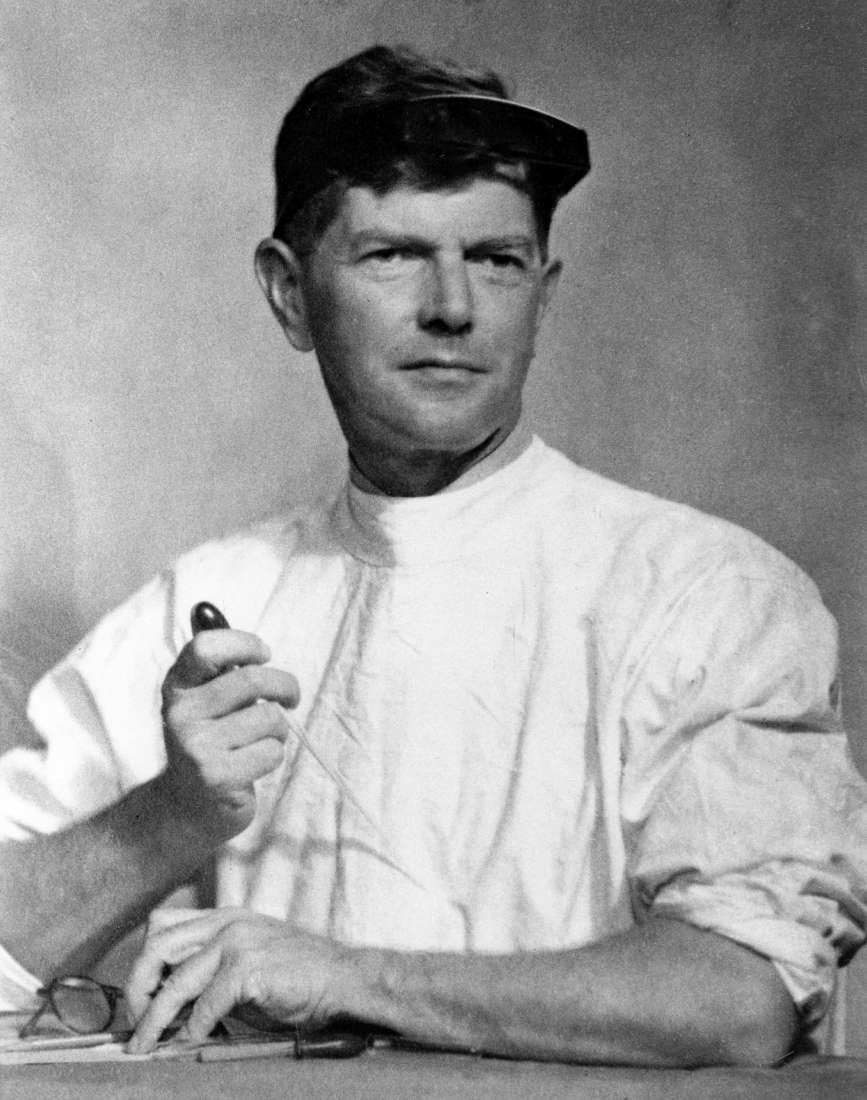

As a small child, Liz Burnet, daughter of Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, is a frequent visitor to the institute. She and her little brother Ian join their father every Sunday, religiously, for a very different ritual to that of other Melbourne households of the era.

Family insight into Burnet’s institute

Burnet would first deliver breakfast in bed to his wife Linda – “Sunday was my mother’s day off” – then feed Liz and Ian as they all listened to Professor (Sir) Sam Wadham on the weekly ABC Radio science program preceding the 9am news.

Then while their neighbors sat in church, Burnet – a reluctant driver, and in Liz’s memory a pretty poor one – would navigate the near empty roads from the family home in Kew to the old Melbourne Hospital, then in Lonsdale Street, the site that would later become the Queen Victoria Hospital and is today the QV shopping precinct.

An unusual playground

Tucked behind the hospital was a small three story building which was the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute – or as it was known colloquially then, the “Wally and Liz”. Burnet would head for his office on the top floor “and look at his eggs”, Liz recalls, while she and her brother went to the basement to join the only other Sunday worker, Reg the animal man.

Ian and I used to do the rounds with Reg feeding the laboratory animals. We thought that by far the most important person at the institute was Reg.

Witnesses to Burnet’s work

Eventually they would climb the wooden stairs to their father’s laboratory, where they would watch, wait and play. “So we knew exactly where he worked and what sort of work he did. We saw the incubators and the eggs with their little windows and how he drilled the holes (using a dentist’s drill).”

One of the perks of the job was that Burnet needed fertilised chicken eggs for his experiments in virology, so any infertile eggs in the delivery were taken home, all the more precious in the lean coming war years. Another happy advantage for young Liz was the fine collection of foreign stamps she was able to acquire courtesy of the correspondence pouring into the already internationally recognised institute.

Sharing in Burnet’s success

Liz would have to wait a couple of decades before enjoying the ultimate perk of being Macfarlane Burnet’s daughter. That came in 1960 with the announcement he would be awarded the Nobel Prize. By then Liz Dexter was married – to Mick, a returned serviceman she met when they were both studying agricultural science at the University of Melbourne. (He still boasts about his luck in earning the affections of the only girl in the year.)

She was also the mother of three young children, but Mick and his mother volunteered to look after them while Liz and her young sister Deb made the then epic journey to Stockholm to attend the ceremony.

The Burnets in Sweden

The occasion was a lavishly grand affair, with everyone from the scientists to Swedish royalty in their finest regalia. “As (Mac’s) turn came, everyone rose while the King presented him with a beautifully bound and illuminated citation, a gold medal and an assignation to receive the money, in Swedish kroner, at a later date.” (Burnet spent most of the money paying for his wife and daughters to join him for the occasion.)

Afterward the laureates and their families gathered with officials and royalty for a banquet in the Great Hall decorated with gold leaf and paintings of mythical Swedish figures. As Dexter recalled in a speech recounting the occasion to the local mothers club soon after her return, “it seems like a dream when I am in the midst of washing up and hanging out clothes in Heathmont”.

An institute family

Today Dexter, 86, suspects she is likely the only person living with intimate memories of life inside the institute in its various incarnations – the Lonsdale Street site, then the Parkville site, and the waves of growth and renovation which have seen it morph into its current form.

“In the original building, the only view was the incinerator and the rubbish tins at the back of the hospital. The top floor was for the virus laboratories, all facing south with top to bottom windows and benches so there was good light but not direct sun. They built the same at the next institute in Parkville. ”

Connection to the institute’s past and present

Dexter suspects that she is the only person to have known all the institute’s directors except the very first, Dr Sydney Patterson, whose tenure finished in 1923.

Charles Kellaway, who employed and nurtured her father, and whom Burnet succeeded in 1944, was a family friend, albeit a distant figure to young Liz. “Mum and dad knew the Kellaways very well. I remember he was a chain smoker and died of lung cancer, and that was when Mac stopped smoking.”

Professor Gus Nossal, who succeeded her father in 1965, was a contemporary and friend to Dexter, and she has strong memories of her father’s careful reflection and motivation in selecting and grooming him to take over the institute.

“I used to hear all the gossip at home. In choosing a successor, it had to be a great scientist, but he was also looking for personality.” Burnet was famously not one for small talk and struggled in social relationships beyond the laboratory, immediate family and intimate friends. He recognised that to succeed in the next era the institute would need a leader who could interact easily and fruitfully with media, politicians and potential donors, Dexter recalls.

He wanted a fine scientist, but he also “wanted someone who was an easy speaker and good with people. Gus ticked every box.

Burnet’s family life

Dexter remembers Burnet as a good father, interested in his children, ready to help with homework and usually home for dinner. He would sit by the fire with a cushion on his knees reading his journals, making entries in his extensive card index.