A rare thymus cell found

T-cells are a type of white blood cell that develop in the thymus, the fan-shaped gland at the base of the neck. But researchers are hazy on precisely how the T-cells develop and differentiate.

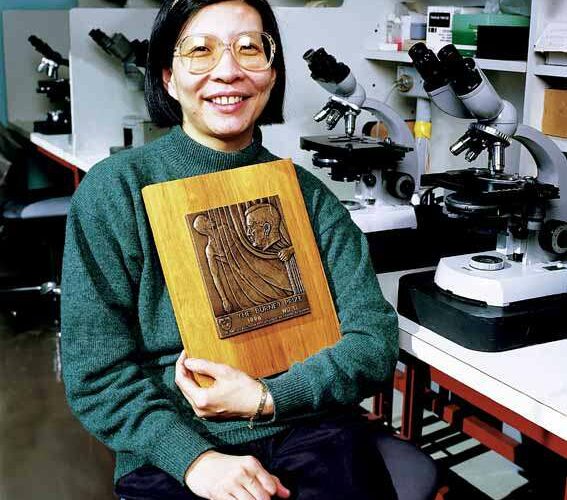

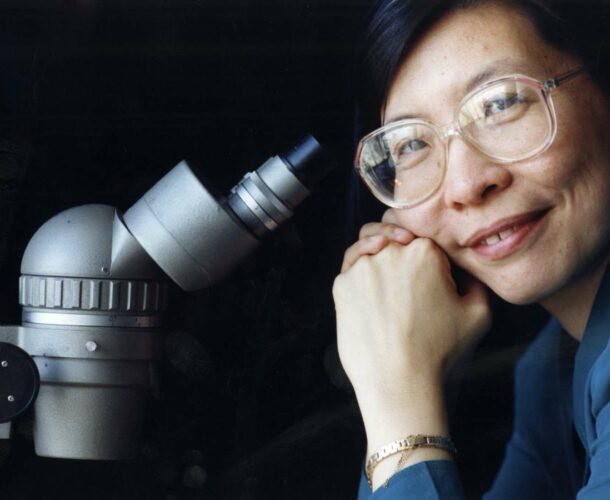

Walter and Eliza Hall Institute Professor Li Wu has answered some of these questions; she has discovered an “ancestor cell” to the T-cell in the thymus. This is a significant discovery, because the more scientists know about how white blood cells develop, the better they can manipulate the process to generate the specific cells needed to fight particular diseases.

Other discoveries followed

Wu and her colleagues found that the same ancestor cell in the thymus also generated dendritic cells, which serve as the body’s alarm system, patrolling for infections. If they find a bacteria or a virus-infected cell they seize and process the foreign material, chopping up the proteins. The protein fragments are then presented on specialised molecules on the dendritic cell’s surface to activate the killer T-cells to fight the infection— and resist any future attack by memorising the infection.

This further discovery showed dendritic cells develop for highly specialised functions — rather than a generalised police force they operate as special squads to deal with specific problems. Wu also found that the ancestor cell in the bone marrow can generate dendritic cells in lymphatic organs, such as the spleen.

Developing immune therapies with dendritic cells

The challenge in developing immune therapies is selecting the right kind of dendritic cells “to activate the body’s troops to fight disease”. This can be done by growing the specialised cells in a tissue culture and injecting them into patients, or even better by injecting the body with cytokines, small molecules that grow dendritic cells in the body.

“And you use different cytokines to promote different dendritic cells.”

Wu says a trial of dendritic cell therapy has shown promise in treating melanoma. “Researchers are also interested in dendritic cell therapy for different kinds of cancers.”

A long lasting relationship across two continents

Professor Li Wu’s relationship with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute spans nearly 30 years and two continents — and it’s due to recurring good news in the immunology lab.

“Every time I thought about leaving we had another discovery,” explains Wu. “And then I’d think, ‘well, better stay now’.”

The association began in the late 1980s, just as China was beginning to forge academic ties with the West. Wu, whose mother is an obstetrician and gynaecologist, was completing a masters in immunology at Beijing Medical University. She was keen to continue with research because “at that time we knew hardly anything about how the body defends itself against disease. But in China the research was preliminary and the funding almost non-existent”.

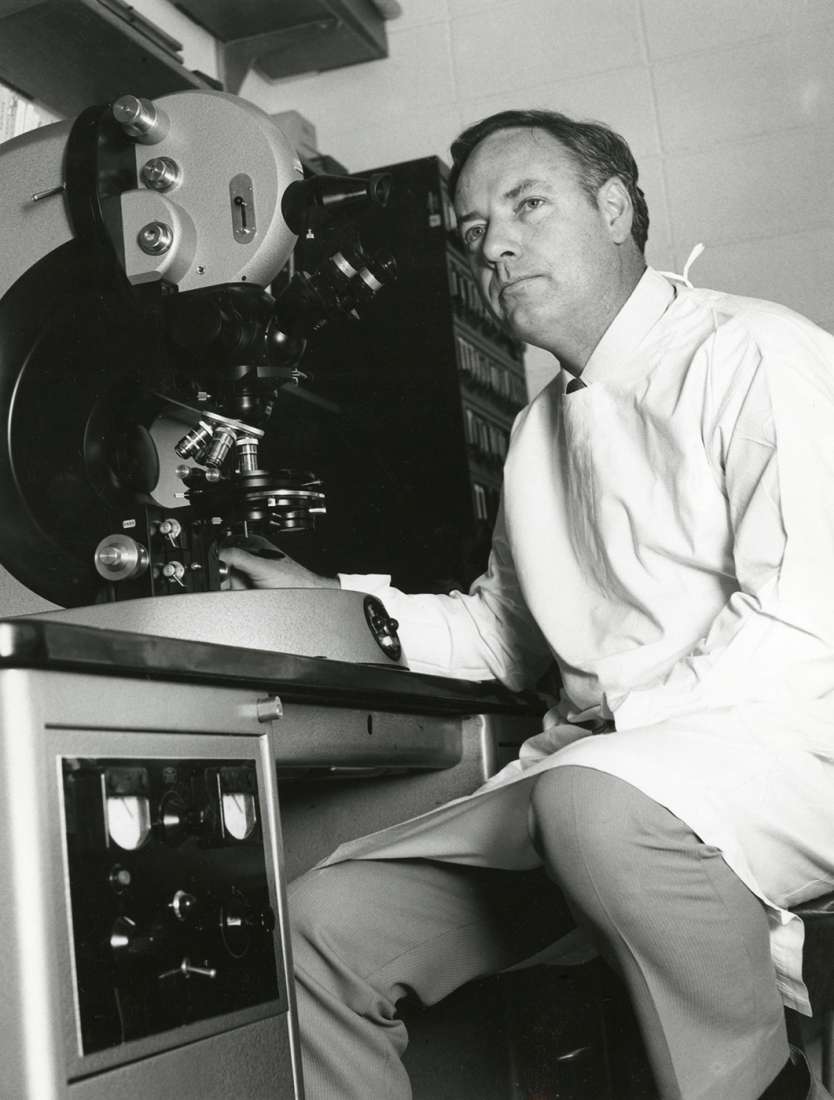

In a case of fortuitous timing, her mentor at the university had recently returned to China after a lengthy stint at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, working with Professor Ken Shortman, whose specialty was discovering subpopulations of cells in the immune system.

“My mentor invited Ken to visit him in China— that’s how we first met. So I talked to Ken, and he said, ‘why don’t you come do your PhD at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute?’”

So Wu arrived at the institute in 1987, armed with a National Health and Medical Research Council scholarship for overseas students. She immersed herself in the study of T-cells, which led to one of the most exciting moments in her career, discovery of the “ancestor cell”.

The upshot of Wu’s discoveries is that she found it difficult to leave the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. From PhD student she metamorphosed into postdoc, independent research fellow, various species of senior fellow and finally, a lab head.

Then in 2010, as part of a push by the Chinese government to persuade its senior academics abroad to return home, Wu was recruited to the newly-established medical school at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, one of the top universities in China. But she retains an honorary fellowship at the institute, and returns often to collaborate on research.

“When it’s school holidays in China I’m usually back here.”