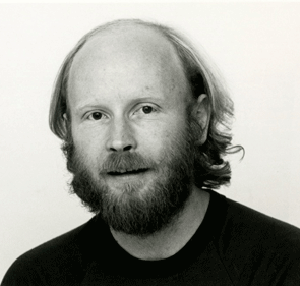

Whilst Dave Kemp was an exceptional scientist and contributed enormously to research, his contributions are much broader. He was a wonderful mentor and central to the development of the malaria field in Australia. Many of us remember fondly Dave’s great love of science and joyful reactions when new results were revealed ‘hot off the developer’. Indeed Dave often made the comment that ‘we have a great life as we are paid to come to work and play’. That was the ethos that he brought to his research and it was infectious, making his laboratory and the Division a ‘fun’ place to work and do science. He didn’t operate a hierarchy, but lead with insight, informality, respect and humour.

Dave retained a great love of music all his life and in the different institutes he worked, including the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, he formed bands that played gigs at various work functions. At the institute he formed the ‘Tandem Repeats’ (a name that came out of the discovery at the institute that many malaria antigen genes consisted of tandem repeat sequences) and many of us remember the parties where his band had the foundations shaking with the music and dancing. He was also an avid ‘rock hound’ and loved heading out into the wilderness to camp under the stars and search for special rocks and minerals.

In 2006, Dave and his wife Katherine (now deceased), a highly committed nurse, moved to tranquil Tallangatta, Victoria, where they were very happy. They are survived by sons Andrew, Ben and Daniel and grandchildren Rachael, Jessica and Ryan.